Engineers To Fire Another Chunk Of Foam At Wing

Engineers investigating the demise

of Columbia have one more crucial test to perform before the

Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) writes its final

report. Monday, they'll use a compressed-gas cannon to fire a 1.67

pound chunk of insulating foam at a shuttle wing panel where they

think debris caused Columbia a fatal wound shortly after lift-off

on January 16.

Engineers investigating the demise

of Columbia have one more crucial test to perform before the

Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) writes its final

report. Monday, they'll use a compressed-gas cannon to fire a 1.67

pound chunk of insulating foam at a shuttle wing panel where they

think debris caused Columbia a fatal wound shortly after lift-off

on January 16.

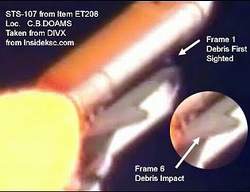

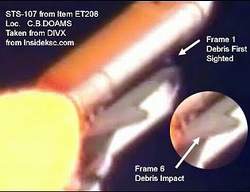

The wing element used in the test at the Southwest Research

Institute in San Antonio (TX) will be completely made of a

reinforced carbon composite taken from the shuttle Atlantis. It's

the same material and configuration that investigators believe was

struck by foam from the external fuel tank 82 seconds after

Columbia launched. Members of the CAIB believe the foam breached

the wing. When Columbia re-entered the atmosphere two weeks later,

investigators theorize the breach allowed super-heated atmospheric

gases to enter the wing structure, beginning a chain of events that

led to the shuttle's disintegration over the skies of East Texas.

All seven crew members aboard were killed.

Already, similar tests have proven that the insulating foam can

indeed cause cracks in the "carbon-carbon" wing panels. G. Scott

Hubbard, director of NASA's Ames Research Center at Moffet Field

(CA) and a CAIB member, says Monday's test will help the board

decide if the January 16th foam impact was a "highly probable" or a

"most likely" cause of the Columbia disaster, according to New York

Newsday.

NASA's Not Waiting

Even in advance of what

NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe has warned will be a blistering

report from the CAIB, NASA and its contractors are making changes

they hope will address the board's findings. Last month, officials

at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville (AL) sat down for

a preliminary design review on a new external fuel tank that won't

use insulating foam at all. Instead, the design uses two small

electric heaters to prevent ice from forming on the fuel tank. This

month, NASA is performing wind tunnel tests and other analyses of

the new design.

Even in advance of what

NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe has warned will be a blistering

report from the CAIB, NASA and its contractors are making changes

they hope will address the board's findings. Last month, officials

at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville (AL) sat down for

a preliminary design review on a new external fuel tank that won't

use insulating foam at all. Instead, the design uses two small

electric heaters to prevent ice from forming on the fuel tank. This

month, NASA is performing wind tunnel tests and other analyses of

the new design.

"There could be some surprises that would make us stop and back

up," said Neil Ott, deputy manager for the external fuel tank

program at Marshall. Still, he's confident that the new design will

be in use by the end of the year.

Problem Not Just On The Drawing Board

The CAIB is slated to release its report to the president,

Congress and the American people before lawmakers leave Washington

for their August recess. Adm. Harold Gehman (USN, Ret.), CAIB

Chairman, has already said as much as half the Columbia report will

deal with non-technical issues like NASA's management and corporate

culture. "We will not tell NASA how to organize," Gehman said

recently. "But we will tell them what needs to be done."

Gehman says the board has been reading up on what he calls "high

reliability" organizations. He points to the FAA as an organization

that doesn't wait for disaster, but learns of its mistakes from

near-tragedies. "You learn as you go," CAIB Consultant Howard

McCurdy told media sources. "The FAA learns from near misses. The

FAA pays a lot of attention to near misses." Another CAIB

consultant says "high reliability" organizations don't linger over

their successes. Instead, they are continually on alert for the

unexpected and the unwelcome, spotting such eventualities and

trying to address them before they can impact the program at

hand.

That mindset goes directly against the NASA mindset before the

Columbia tragedy. On at least seven flights previous to STS-107,

controllers and engineers virtually ignored chunks of insulating

foam falling from the external tank and impacting the orbiter.

NASA, in fact, eventually viewed such debris strikes as being

within the parameters of normal flight.

A similar assumption is thought to have contributed to the 1986

Challenger disaster. Moments after launch, Challenger exploded.

That accident was eventually attributed to erosion within the

O-rings of the solid rocket boosters.

"What are the other things that are continuously sending you

signals," Gehman asked in April. "I'd like to find some other

things that are kind of strange looking, kind of funny looking and

NASA says we're going to live with them."

"That's really been a bedeviling question," O'Keefe said

recently. "It's the 'How do you diagnose the next thing around the

corner?'" But he said the agency must find ways to sift through

documentation and "not get bogged down with something that turns

into this compendium of stuff that doesn't tell you anything."

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (06.29.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (06.29.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (06.29.25): Gross Navigation Error (GNE)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (06.29.25): Gross Navigation Error (GNE) Classic Aero-TV: Anticipating Futurespace - Blue Origin Visits Airventure 2017

Classic Aero-TV: Anticipating Futurespace - Blue Origin Visits Airventure 2017 NTSB Final Report: Cirrus SR22

NTSB Final Report: Cirrus SR22 Airborne Affordable Flyers 06.26.25: PA18 Upgrades, Delta Force, Rhinebeck

Airborne Affordable Flyers 06.26.25: PA18 Upgrades, Delta Force, Rhinebeck