New Anthrax Vax May Prove More Palatable

The next-generation anthrax vaccine, based on a decade of work

at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases,

is now moving into not one, but four clinical trials.

The group at the institute did the legwork for the current

vaccine candidates by singling out which protein in Bacillus

anthracis -- the bacterium that causes anthrax -- signals the

body to produce immunity to the disease.

Early studies established definitively that the protein called

"protective antigen" was just the component the vaccine would

require, said Dr. Arthur Friedlander, a senior scientist at

USAMRIID who directed the group's long-term effort. After

discovering the protein, researchers took the gene that codes for

protective antigen and used recombinant DNA technology to try to

produce the protective antigen in three expression systems:

bacteria, yeast and viruses.

Ultimately, the team found bacteria was the best for producing

the protein, and decided to grow the protective antigen in a

non-disease causing strain of B. anthracis. The resulting

recombinant protective antigen, or rPA, should provide a high

degree of safety in a vaccine because it's just one building block,

a single protein of the organism that can produce an immune

response.

Researchers then proved it was effective in the best animal

model available, the non-human primate. "What we did was identify

it, purify it to a very high degree and showed that this protein by

itself was protective in the most relevant animal model of human

inhalational anthrax,"

Friedlander said.

Research Locations Pinpointed by Army (More TFRs Coming?)

To date, two clinical trials that use the B.

anthracis-based rPA are underway. VaxGen, based in Brisbane

(CA), started its clinical trials at Baylor College of Medicine,

Texas; Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta; Johns

Hopkins University in Baltimore and Saint Louis University Health

Sciences Center. The test is under a contract from the National

Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases.

In a collegial effort, the National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases, USAMRIID and the Joint Vaccine Acquisition

Program have undertaken a Phase I clinical trial at the University

of Maryland using a version of the original USAMRIID formulation

manufactured at the National Cancer Institute Frederick (MD).

The University of Maryland trial will help advance the

development of the other vaccines, said Dr. Lydia Falk, director of

the Office of Regulatory Affairs, in the Division of Microbiology

and Infectious Diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases.

"We can begin to compare the responses we see in humans to what

had been observed in animals," she said. "That's a critical part of

the development of these vaccines. The more preliminary

investigative work that we can do, the more it benefits the entire

field. Our hope is that the information we gain will be able to add

to those building blocks that would lead to an accelerated

development plan."

FDA Won't be a Roadblock

The formulation being used in that

trial won't be pushed toward Food and Drug Administration

licensing. "The product that is available and the one that was used

during USAMRIID's preclinical studies had the rPA protein in one

tube and an aluminum adjuvant in another tube, and before you

injected it, you mixed the two," Falk said. "That's not an easy

formulation to take to licensure." However this trial design will

determine the value of including an adjuvant in the final vaccine

formulation.

The formulation being used in that

trial won't be pushed toward Food and Drug Administration

licensing. "The product that is available and the one that was used

during USAMRIID's preclinical studies had the rPA protein in one

tube and an aluminum adjuvant in another tube, and before you

injected it, you mixed the two," Falk said. "That's not an easy

formulation to take to licensure." However this trial design will

determine the value of including an adjuvant in the final vaccine

formulation.

Two companies are currently using rPA grown in E.

coli to create their next generation anthrax vaccine

candidates. An rPA vaccine from the UK-based Avecia, under a

contract with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious

Disease, will soon start Phase I clinical trials.

The second company, Dynport Vaccine Company, LLC, which licensed

its rPA product from Avant, began its Phase I clinical trial April

28. The trial is being conducted by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation

in Rockville (MD), which routinely pursues vaccines for HIV for the

military.

Because the foundation had an HIV vaccine candidate that used

rPA as one of its two components "we decided to reprioritize our

activities and commit to evaluating this protective antigen after

the anthrax mail attacks in October 2001," said Dr. Merlin Robb of

the Henry M. Jackson Foundation, the principal investigator for the

foundation's clinical trial. "(The rPA) was ready to go into humans

to evaluate it for an anthrax indication. We sensed that it was a

higher national priority."

Although the rPA vaccines are on an advanced development path

toward Food and Drug Administration licensure, USAMRIID scientists

still lend their expertise to vaccine manufacturers and the

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

"Their contributions can't be overstated," said Dr. Ed Nuzum,

the project officer providing technical oversight for the two

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases contracts

with Avecia and VaxGen. "Because of the work done at USAMRIID, as

well as its counterpart in the United Kingdom, the Defence Science

and Technology Laboratories, the rPA-based vaccine candidates are

the most advanced second generation anthrax vaccines."

USAMRIID's early development work regarding animal

studies and assay development will also be critical for developing

animal models for Food and Drug Administration approval under the

"Animal Rule." The rule, effective in July 2002, permits use of

data from animal studies when efficacy studies of new drugs or

biological products against chemical, biological, radiological or

nuclear substances in humans is impossible because of the rarity of

the disease or because human exposure to potentially lethal agents,

like anthrax, is unethical.

"This is the first test case of the concept of licensing a

vaccine based on animal efficacy data and trying to correlate that

with the human immune response," Friedlander said.

Nuzum said he thinks the rPA vaccines are potentially the best

vaccines to be going forward for licensure under the animal rule

largely because of the work done at USAMRIID and DSTL. "The data,

models and assays really are essential to the foundation for the

work we're doing now," he said.

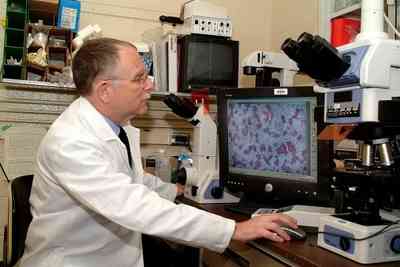

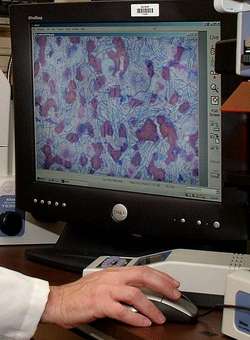

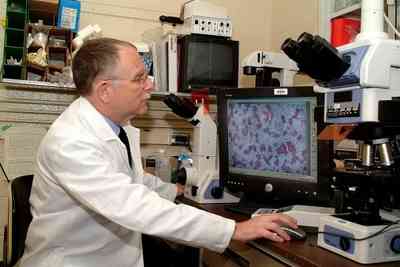

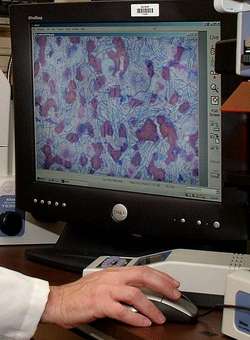

[Thanks to Karen Fleming-Michael, reporter at Fort Detrick (MD),

and the American Forces Press Service. Photo by Larry

Ostby --ed.]

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.12.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.12.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.12.25): Land And Hold Short Operations

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.12.25): Land And Hold Short Operations ANN FAQ: How Do I Become A News Spy?

ANN FAQ: How Do I Become A News Spy? NTSB Final Report: Cirrus Design Corp SF50

NTSB Final Report: Cirrus Design Corp SF50 Airborne 12.08.25: Samaritans Purse Hijack, FAA Med Relief, China Rocket Fail

Airborne 12.08.25: Samaritans Purse Hijack, FAA Med Relief, China Rocket Fail