Changes Would Save Time, Fuel

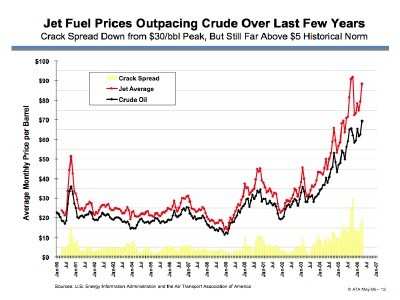

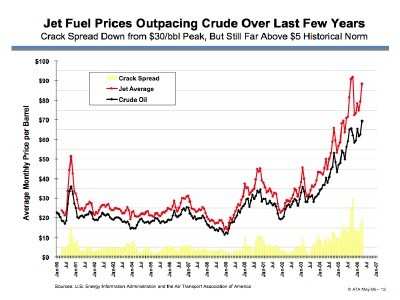

The Air Transport Association, the lobbying group for the major

United States Part 121 airlines (passenger and cargo), has long

been the authoritative voice of the airline industry. In the ATA's

latest briefing on the contentious fuel issue, the organization

mentions several potential ATC changes that might lead to time and

fuel savings.

The slide begins by praising the 2005 introduction of RVSM as an

example of the sort of procedural improvement that can save gas and

increase system capacity while maintaining an equivalent level of

safety. RVSM, Reduced Vertical Separation Minimums reduces

mandatory vertical separation between flight levels 290-410

(inclusive) from 2,000 feet to 1,000 feet, providing a theoretical doubling of traffic

throughout.

Are there more potential gains to be found in the system? The

ATA thinks so.

Here's ATA's list -- with a little of ATA's expanding text, and

our comments. Due to the amount of information involved, we've

split this into two parts. Today, we look at ATA's wish for

the FAA to expand the deployment of RNAV at major airports...

as well as for the agency to reconsider the current 250-knot "speed

limit" below 10,000 feet MSL.

On Thursday, we'll look at some of the ways ATA proposes to

reduce delays and holding times, and we'll offer our summary of the

situation.

The Wish List

- Accelerate RNAV deployment at hub airports; delegate

development of procedures. RNAV (Area Navigation)

provides more lateral freedom, so that airplanes use the whole

sky instead of the narrow, constricted pipelines of airways and

jetways.

ANN Take: Presumably they're talking about a

terminal version of Free Flight, or at least a greater number of

arrival/departure corridors for transport aircraft; with

development of the procedures offloaded to the individual lines or

their contractors. (Already, at present, an operator can develop a

Required Navigation Performance procedure of his own and staff it

through FAA). Real RNAV capability is a lot more widespread in GA

than in the airline fleet at present, but ATC seems to be slow on

the uptake. What's been holding it back, of course, is the

airlines' reluctance to embrace this technology. Flying from beacon

to beacon like Slim Lindbergh on the mail run in 1925 needs to die.

But having aircraft traveling at arbitrary altitudes and speeds, in

arbitrary directions, is going to tax controllers -- and their

computers.

And then, there's the effect on reliever airports -- which in

turn reflects back on the air carrier fields. Given that many

reliever airports are in close proximity to air carrier airports,

and separation of approach and departure paths to reliever airports

depend on the air carrier airplanes flying through distinct arrival

gates, the possibility exists that this proposal would increase

throughput at air carrier facilities at the expense of IFR capacity

at nearby reliever airports. This in turn is one of the few

scenarios where the hoped-for explosion of VLJ traffic in and out

of relievers would have a noticeable impact on air carrier

operations in the terminal environment. Imagine an Atlanta metro

area where traffic into KATL does not adhere to current routings,

but overflies the very busy reliever airports at low altitude.

No question that GPS can make for routings and fuel savings for

air carrier airplanes, but there would likely still need to be some

level of SID/STAR routings to deconflict with GA traffic at

outlying airports. At least with GPS there could be many more

transport corridors than a ground-based navigation system

provides.

- Reconsider rule limiting speeds below 10,000 feet to 250

knots; some aircraft may operate more efficiently at higher speeds

(especially on climb-out) but are prevented from doing so (note:

also allows controllers greater flexibility to manage air

traffic)

ANN Take: One reason for this reg (FAR

91.117(a)) is that, at higher speeds, see-and-avoid isn't

practical, as a couple of well-known accidents where military

aircraft centerpunched loitering GA machines have illustrated. ATA

tends to assume that their birds are the only ones in the sky; it

ain't necessarily so. The basic problem is one of deconfliction

with aircraft that are not in the system; deconfliction with IFR

aircraft appears to pose no problems.

If that hurdle could be overcome, lifting this limit would be a

benefit to airline and to business jet operators (especially as

newer, faster jets come online in the next two decades). It would

drive Boeing and Airbus wild with frustration because their latest

planes are designed with this limit in mind, and might have been

more efficient without it.

From the GA point of view this remains an alarming proposal

without a way for participating aircraft to see and avoid

nonparticipating aircraft. We're keenly aware that in a GA-airline

midair, the finger of blame points to GA even when the airliner's

CVR reveals the crew yukking it up about having lost sight of the

Cessna they're about to hit. (Not that there isn't usually enough

blame to go around in any of these crashes). The inability of the

military to completely prevent even F-16s and Tornados, whose

onboard radar detects even non-transponder aircraft, from the

occasional midair is not encouraging about a future filled with

airliners traveling at 300+ knots without such equipment.

See-and-avoid is the basis of aircraft separation even for IFR

airplanes when in Visual Meteorological Conditions. See-and-avoid

permits a much greater airport capacity for air carrier aircraft

when conditions are VMC -- picking on ATL again, think about

airline flight delays any time it's even marginal VFR at the

airport. Depending on IFR separation requirements at all times to

permit higher speeds would condemn air carrier airports to their

low-capacity modes all of the time, not just when weather is

poor.

Finally, birds (birds in the literal sense) never file IFR and

don't carry transponders, and civil aircraft windshields are not

certified for bird strikes at high speeds (or multiple-bird strikes

for that matter). While birdstrike safety certification standards

have resisted worldwide harmonization, US standards are relatively

close to those of other authorities. FAA tests to 250-280 knots,

the Air Force to 550 knots. The speed limit rule was imposed in

North America for the principal purpose of bird-strike safety, and

a thorough 2005 study in Canada presented data supporting the

retention of the limit.

"[A] 20 percent increase in aircraft speed from 250 to 300 KIAS

results in a 44 percent increase in impact energy during a bird

strike," the authors summarized. "Clearly the speed of the aircraft

and engine rotation speed are more important in a collision than

the size of the bird and more controllable than the size of the

bird." (.pdf here). The study notes that a

previous FAA experimental study of higher speeds in Texas in 1998

was cut short as unsafe. That document contains some chilling

stories of bird strike damage, casualties and near-casualties.

As proposed here, then, the ability to operate at unrestricted

speed benefits the airlines by increasing on-time performance for

late-launched flights, and may provide some fuel

savings. Until a near-foolproof system for avoiding bird

strikes is incorporated, however, those changes may come

at the expense of a probable increase in aircraft lost through

bird strikes and midairs.

We think that if you asked the passengers on those doomed

aircraft, they'd pay a few dollars more in order not to die.

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.28.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.28.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.28.25): Decision Altitude (DA)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.28.25): Decision Altitude (DA) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.28.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.28.25) Airborne-Flight Training 04.24.25: GA Refocused, Seminole/Epic, WestJet v TFWP

Airborne-Flight Training 04.24.25: GA Refocused, Seminole/Epic, WestJet v TFWP Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.29.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.29.25)