Brilliant 'Save' During 'Enduring Freedom'

Landing an aircraft on narrow strip

of a rocking carrier deck at sea is what sets Naval aviators apart

from all others. Now add fire, smoke and fumes to an already

complicated situation and you have an idea of what S-3 pilot Cmdr.

Ron Carlson was facing during a night flight that could have ended

in disaster but instead earned him one of the most coveted awards

in the military.

Landing an aircraft on narrow strip

of a rocking carrier deck at sea is what sets Naval aviators apart

from all others. Now add fire, smoke and fumes to an already

complicated situation and you have an idea of what S-3 pilot Cmdr.

Ron Carlson was facing during a night flight that could have ended

in disaster but instead earned him one of the most coveted awards

in the military.

Capt. Steve Eastburg, manager of the Maritime Patrol

Aircraft Program (PMA-290), presented Cmdr. Ron Carlson,

NAVAIR’s S-3 Program Manager, the Distinguished Flying Cross

at PMA-290’s family day celebration on June 25 in recognition

of his extraordinary achievement during aerial flight.

"I am honored and very

appreciative of this award but I was just doing my job," said

Carlson, the self-described average American. "I was doing what

they pay me to do – I was aviating, navigating and

communicating."

"I am honored and very

appreciative of this award but I was just doing my job," said

Carlson, the self-described average American. "I was doing what

they pay me to do – I was aviating, navigating and

communicating."

The incident Carlson was honored for happened January

9, 2002 over the North Arabian Sea. At the time, he was the

commanding officer of Sea Control Squadron 32 (VS-32) and was

deployed onboard USS Theodore Roosevelt in support of

Operation Enduring Freedom. His flight that moonless night began as

hundreds of routine refueling missions had before but ended unlike

any other.

Carlson and his naval flight officer Lt. j.g. Tim Gantz

catapulted from the deck of the Roosevelt at 7 p.m. and

returned 20 minutes later - about an hour sooner than planned. As

they approached 14,000 feet, Carlson was alerted by the number 1

bleed leak light followed by the number 2 bleed leak light,

indicating an environmental control system compartment fire.

"At first, I wasn’t that concerned," Carlson

said.

"At this point in my career with no serious incidents before,

things had become routine and I had almost lost track of the

dangers of this business. When the smoke started rolling in, it got

my attention real fast."

The fire caused the loss of the main hydraulic system and nearly

all flight-related electrical systems. Smoke and fumes filled the

cockpit preventing Carlson from seeing Gantz sitting just two feet

to his right. Carlson was able to get out one radio transmission to

the ship before all communication was lost. The landing gear would

not go down, the flaps were not responding and Carlson saw no light

on the horizon. The thought of ejecting crossed his mind.

"I didn’t really want to get out," said Carlson, who knew

there was no guarantee that they would be found under those

circumstances.

Under the pitch-dark skies off the coast of Pakistan, Carlson

somehow managed to visually locate the Roosevelt but did a wave-off

on his first approach because he wasn’t comfortable with the

landing gear indications. Without being able to slow the S-3 down

for the landing, Carlson approached the deck again at 185 mph --

about 60 mph more than usual -- and performed a no-flap, visual

landing with no radio communication while on fire. As he caught the

third wire, the right main and nose landing gear collapsed on

impact. The right fuel tank caught fire once it made contact with

the carrier deck and the aircraft skidded to rest on its side in

flames. As Carlson and Gantz exited the S-3 through its emergency

hatch, the aircraft was doused with water and foam by the

ship’s firefighters.

"He did an incredible job landing that aircraft that night,"

Gantz said. "What he did was above and beyond the call of duty and

I have nothing but respect and admiration for him as a person and

as a pilot."

It was a bone-jarring landing but Carlson and Gantz walked away

with little more than a few cuts and bruises. Some members of

Carlson’s squadron said divine intervention played a part in

keeping those two alive that night.

Looking back, there were

signs that Carlson was there for a reason. Months after the mishap,

another officer relayed to Carlson his observations: Carlson was

supposed to have been relieved of his command two months earlier

but was extended because of operational necessity. He was

originally scheduled for a day flight on January 9 but personally

requested a night flight. And, there were two other airplanes

launching at that time that he could have easily been assigned to,

and his NFO that night was a former minister.

Looking back, there were

signs that Carlson was there for a reason. Months after the mishap,

another officer relayed to Carlson his observations: Carlson was

supposed to have been relieved of his command two months earlier

but was extended because of operational necessity. He was

originally scheduled for a day flight on January 9 but personally

requested a night flight. And, there were two other airplanes

launching at that time that he could have easily been assigned to,

and his NFO that night was a former minister.

"When I took command of VS-32, my only wish was that everyone in

the squadron came home," Carlson said. "I guess unknowingly I was

making that come true."

Carlson said he could not explain why things happened as they

did. But, he did say that his 20 years of naval training and

experience got him through the most dangerous and life-threatening

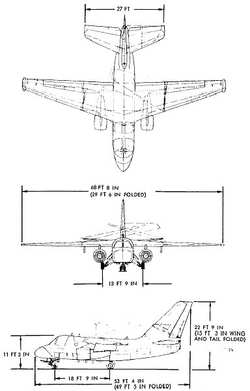

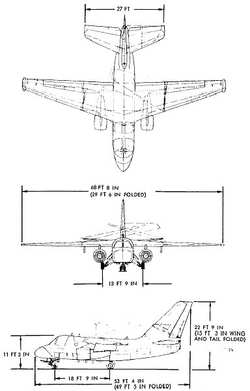

situation in his career. Carlson has logged more than 4,200 flight

hours in the S-3 and has made 800 arrested landings at sea.

"I have a lot of pride in my work," said Carlson, who from a

small town in Michigan came to the Navy by earning an ROTC

scholarship. "I strive to be the best that I can be in everything I

do. I worked hard for 20 years and learned my stuff."

Carlson is the only S-3 pilot to be awarded the Distinguished

Flying Cross and with that aircraft entering the sundown of its

service life, he may be the only S-3 pilot in history to receive

this distinction.

This is what we all train and prepare for but the way I got this

award is not something I want someone else to go through," he

said.

Carlson was back in the air after taking just one day off from

flying. He flew two times a day for four days before requesting the

same flight at the same time with the same NFO.

"I had some reservations," Carlson said, "but I knew I had to

get over that."

After returning from that deployment, Carlson’s shore duty

assignment brought him, his wife and three kids to St. Mary’s

County where he now works for NAVAIR. Surprisingly, little has

changed in his life since that 20-minute flight over the Arabian

Sea.

"I know a lot of people who have gone through life-threatening

situations and they have made significant changes in their lives,"

Carlson said. "I haven’t done anything extreme but I do enjoy

the little things in life more."

[Thanks to Renee Hatcher, PEO(A) Public Affairs --ed.]

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (06.30.25): Ground Stop (GS)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (06.30.25): Ground Stop (GS) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (06.30.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (06.30.25) Aero-News: Quote of the Day (06.30.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (06.30.25) NTSB Final Report: ICON A5

NTSB Final Report: ICON A5 Airborne Affordable Flyers 06.26.25: PA18 Upgrades, Delta Force, Rhinebeck

Airborne Affordable Flyers 06.26.25: PA18 Upgrades, Delta Force, Rhinebeck