Massive, Sustained, Combined-Forces Attack In Iraq

If the Bush administration gets its way, the

United States will once again be at war with Iraq before the end of

the month. The air campaign in this Second Gulf War will be much

different than the 43-day long air campaign in 1991. It will be

much more foreceful, much more precise and will coincide with the

launching of ground operations. The combined effect on Iraq's

political and military leadership: "Shock and awe"

If the Bush administration gets its way, the

United States will once again be at war with Iraq before the end of

the month. The air campaign in this Second Gulf War will be much

different than the 43-day long air campaign in 1991. It will be

much more foreceful, much more precise and will coincide with the

launching of ground operations. The combined effect on Iraq's

political and military leadership: "Shock and awe"

More Than A Name

The concept of "shock and awe" is actually

military doctrine at the Pentagon. The man who wrote it is Dr.

Harland Ullman at the Center for Strategic and International

Studies in Washington (DC).

The concept of "shock and awe" is actually

military doctrine at the Pentagon. The man who wrote it is Dr.

Harland Ullman at the Center for Strategic and International

Studies in Washington (DC).

"The notion here is that we want to affect, influence and

control both the will and perception of the Iraqi political and

military leadership to get them to do what we want them to do" -

which is to surrender en masse and give up dictator Saddam Hussein.

"The way to do that is to just impose on the Iraqi political and

military leadership a condition of complete hopelessness, where

they are so surrounded, so outgunned, so outnumbered that their

only option is to quit. We now have the technology and the

intellectual smarts to do that."

Indeed, the United States has amassed a huge military force in

the Persian Gulf. Six aircraft carrier battle groups are in the

Gulf, along with the British group centered on the HMS Ark

Royal.

Hundreds of allied warplanes are now based in Qatar, Bahrain,

Saudi Arabia and elsewhere. More than 250,000 American and British

troops are on the ground, pointed at Baghdad and ready to

fight.

Weapons Not Different - Just More Of Them

The number of precision aerial weapons, whether

missiles or aircraft-delivered guided munitions, is staggering,

compared to the last Gulf War a dozen years ago. The United States

plans to deliver up to 3,000 of these missiles and bombs on Baghdad

in the very first few seconds of the conflict.

The number of precision aerial weapons, whether

missiles or aircraft-delivered guided munitions, is staggering,

compared to the last Gulf War a dozen years ago. The United States

plans to deliver up to 3,000 of these missiles and bombs on Baghdad

in the very first few seconds of the conflict.

"What we have here is the opportunity to employ thousands of

weapons against specific targets close to simultaneously. They'll

destroy only those targets instead of causing a lot of damage

around them.

"We have extraordinary precision here," said Dr. Ullman. "In

this campaign, it'll take one or two weapons to destroy a target,

where, in the old days, it would have taken 50 or 60. Even in the

Gulf War, we only had 10 percent smart weapons."

The United States has also become much more adept

at precision targeting, said Ullman.

The United States has also become much more adept

at precision targeting, said Ullman.

"Go back to World War II," he said, in a telephone interview

with the USA Radio Network, "say you wanted to destroy a German

power plant. We'd send in, literally, hundreds of B-17s. They'd

drop thousands of bombs and we'd demolish everything. Now, because

we know a lot more, we realize that a power plant is very

vulnerable (to the destruction of) either a transformer or a

particular set of power lines or a control room. So, if you destroy

the transformer, the power lines or the control room, in essence,

you've destroyed the power plant - without having to destroy (the

entire) power plant."

Aerial Jujitsu

That same targeting analysis has been applied to the Iraqi Army

and particularly to the Iraqi Republican Guard, Saddam Hussein's

elite military force. "You really focus on the minimum pressure

points. This is a kind of jujitsu. If you take out those pressure

points and render (the Iraqis) impotent or incapable of operating,

in essence, you have made that part of the Iraqi Army impotent. You

put the Iraqis in a position of desperation. So much so,

psychologically that the only option they can consider is to

quit."

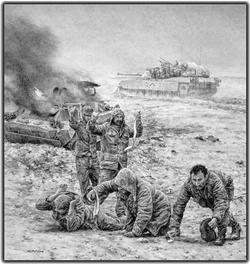

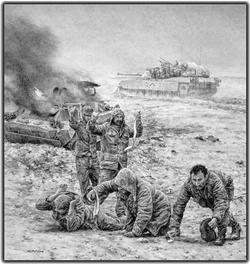

Note the concept of bringing about the collapse of Saddam's

forces without actually destroying them. "There is a moral

imperative, and we have embraced this, to minimize casualties. I'm

a veteran and a victim of the Vietnam war where we never did that.

The legacy is that we really appreciate now the need for minimum

casualties on our side - and certainly civilian casualties. So this

is going to be one of the requirements for planning: 'How can we do

this as - antiseptically is a bad word - as efficiently as possible

to minimize casualties on all sides."

That idea seems to bear upon "life after Saddam." Supposing a

regime change, Ullman says, we're going to need the remnants of

Iraq's army to help restore and maintain order as the country

transitions from a dictatorship, to military rule, and then to

self-elected civilian rule. "Besides," said Ullman, "if we destroy

the Iraqi army on a wholesale basis hoping to demoralize them, it

might just have the opposite effect. So the notion here is to hold

them wholly vulnerable without necessarily having to kill or attack

them, because that generates the strongest psychological force that

will cause them to do our will and to surrender with a minimum of

fighting on their side."

More Than Smart Bombs

Dr. Ullman said the initial campaign of "shock and

awe" will come, not just from above, but on the ground as well.

"It's not just launching weapons on targets. It's the simultaneous

use of ground forces, of psychological warfare and information

operations, so that all of a sudden, the enemy feels entirely

hopeless and impotent. They'll feel that American forces are on the

ground everywhere and nowhere. They'll know we're there, they'll

know we're doing things to them, but they won't know where we are.

The use of these munitions, whether they're cruise missiles or JDAM

stand-off munitions in large quantities - the simultaneous nature

of these attacks against specific targets, with great precision,

will impose upon the Iraqis the sense of hopelessness. We hope this

will lead them to surrender."

Dr. Ullman said the initial campaign of "shock and

awe" will come, not just from above, but on the ground as well.

"It's not just launching weapons on targets. It's the simultaneous

use of ground forces, of psychological warfare and information

operations, so that all of a sudden, the enemy feels entirely

hopeless and impotent. They'll feel that American forces are on the

ground everywhere and nowhere. They'll know we're there, they'll

know we're doing things to them, but they won't know where we are.

The use of these munitions, whether they're cruise missiles or JDAM

stand-off munitions in large quantities - the simultaneous nature

of these attacks against specific targets, with great precision,

will impose upon the Iraqis the sense of hopelessness. We hope this

will lead them to surrender."

Aerial bombardment, however, will be the key to "shock and awe."

Ullman uses the example of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At the end of

the Second World War, the United States faced the daunting

likelihood of invading Japan to force them to surrender. Instead,

the United States deployed the first - and so far, the only -

nuclear weapons ever fired in anger. "The notion here of 'shock and

awe' is that we changed the will and perception of an enemy that,

prior to the bombings, was suicidal. We did it because we shocked

them and awed them. Basically, the Japanese could not understand

that one airplane, one bomb, could have that destructive

power."

It is, Ullman admitted, something of a gamble.

Just as the Japanese might have chosen to fight on in spite of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Iraqis, he said, could decide they're

just not that impressed with the "shock and awe" doctrine. "This

may be the most brilliantly executed military strategy," Ullman

said. "It may do all the things that we've hoped. The Iraqis may

decide that they're not going to tolerate an invasion, that they

will retreat to Baghdad and there'll be a horrible battle around

Baghdad. That could happen. In wartime, you have to plan for the

worst, but hope for the best. There's no guarantee in war. Things

could go very badly."

It is, Ullman admitted, something of a gamble.

Just as the Japanese might have chosen to fight on in spite of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Iraqis, he said, could decide they're

just not that impressed with the "shock and awe" doctrine. "This

may be the most brilliantly executed military strategy," Ullman

said. "It may do all the things that we've hoped. The Iraqis may

decide that they're not going to tolerate an invasion, that they

will retreat to Baghdad and there'll be a horrible battle around

Baghdad. That could happen. In wartime, you have to plan for the

worst, but hope for the best. There's no guarantee in war. Things

could go very badly."

Even so, Ullman said, "shock and awe" is still a viable plan of

battle. "If we're looking to win this in the quickest, most

decisive possible way, with minimum casualties, this offers us the

best alternative. But we have to understand that war is a bloody,

dangerous, nasty business where things go wrong. I've been there.

I've experienced that. This could happen (in Iraq). We have to plan

for the worst and hope for the best."

ANN Weekend Editor Pete Combs conducted his interview with

Dr. Ullman for his award-winning daily news program "America

United: The War on Terror," a service of the USA Radio

Network.

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.06.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.06.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.06.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.06.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF) ANN FAQ: Q&A 101

ANN FAQ: Q&A 101 Classic Aero-TV: Virtual Reality Painting--PPG Leverages Technology for Training

Classic Aero-TV: Virtual Reality Painting--PPG Leverages Technology for Training Airborne 05.02.25: Joby Crewed Milestone, Diamond Club, Canadian Pilot Insurance

Airborne 05.02.25: Joby Crewed Milestone, Diamond Club, Canadian Pilot Insurance