Race To Complete Plans For Shuttle Replacement

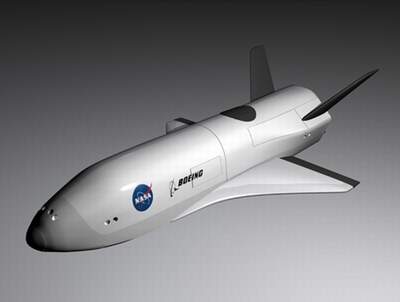

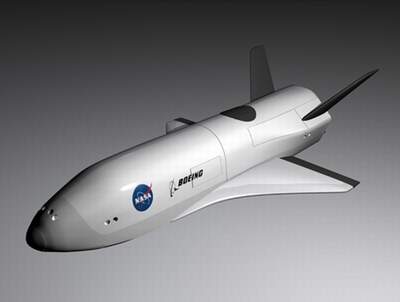

Nobody is sure what the Orbital

Space Plane will finally look like -- whether it'll be a winged

vehicle or a capsule. But one thing is for certain. The OSP is on

the fast-track.

Nobody is sure what the Orbital

Space Plane will finally look like -- whether it'll be a winged

vehicle or a capsule. But one thing is for certain. The OSP is on

the fast-track.

By 2008, the OSP is supposed to be up and flying as a rescue

vehicle for the International Space Station. By 2012, it's supposed

to be ready for two-way crew transfers.

"We're making progress, a lot of good progress," says Dennis

Smith, Orbital Space Plane program manager at NASA's Marshall Space

Flight Center in Huntsville (AL). "The contractor teams are

performing well and they are working hard. We are treating this as

a kind of partnership, and we're working well together."

Smith says the OSP is designed as an economy model. NASA doesn't

plan to spend any more than $13 billion on its development before

2009. "We're the first program that is being implemented under

full-cost accounting," says Smith.

But not everyone is happy with the OSP. Some see it as the

ultimate in retro-engineering. "It's a giant leap backwards,"

complains one space industry analyst. "NASA has an open checkbook

right now to get the shuttle flying. The problem is that they are

looking for the cheapest solution in terms of a backup, and that

would be the OSP. But even that's not cheap."

The skepticism extends to some offices on Capitol Hill.

Congressmen Sherwood Boehlert (R-NY) and Ralph Hall (D-TX) lead the

House Science Committee. "Mr. Hall and I have called on NASA not to

move ahead yet with a Request for Proposals for the Orbital Space

Plane," says Boehlert, speaking at a forum on NASA's future. "We're

not, by the way, calling for a complete halt to the program, but we

don't want to start taking steps that seem irrevocable."

Indeed, even as companies like Lockheed-Martin put manpower and

resources on the line for the OSP, they're doing it with frequent

glances over their corporate shoulders. "We're worried as much as

keeping the program sold at NASA Headquarters and on Capitol Hill

as we are about winning the program," says former astronaut Michael

Coates, now a VP for Advanced Space Transportation at

Lockheed-Martin.

What Will It Look Like?

So far, the capsule advocates seem to be winning -- especially

if one major goal is to get the OSP up and running ASAP. "A winged

vehicle would take a long time to develop," says Coates.

Dale Myers agrees. He was a key engineer on the Apollo project.

Testifying before the House Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics

earlier this year, Myers said, "It appears to me that the robust

launch escape system of Apollo, which worked over a wide range from

the launch pad to high altitude, will be hard to beat in a winged

vehicle."

All eyes are on NASA now. John Logsdon, Director of the Space

Policy Institute at George Washington University's Elliott School

of International Affairs, was a member of the Columbia Accident

Investigation Board (CAIB). "The OSP program is extremely important

in terms of reflecting, first of all, whether NASA's really going

to change its behavior and not try to pursue a project that's

driven by [NASA] center interests and contractor interests but is

driven by national interests. I fall back on what the CAIB said.

Crew transfer to and from the space station, maximized for safety,

period. There's no reason in the world that should cost $12

billion."

Whether NASA plans to make the OSP a simple craft dedicated to a

simple purpose -- rotating crews and shuttling small amounts of

cargo to the ISS -- is still up in the air. The question for

Logsdon and others who think like him is: Will this project become

something like a Congressional spending bill -- so overloaded with

pork and wishful thinking that it can't even get off the

ground?

ANN FAQ: How Do I Become A News Spy?

ANN FAQ: How Do I Become A News Spy? Aero-News: Quote of the Day (10.28.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (10.28.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.28.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.28.25) NTSB Final Report: Aviat Aircraft Inc A-1B

NTSB Final Report: Aviat Aircraft Inc A-1B ANN's Daily Aero-Term (10.28.25): Hold For Release

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (10.28.25): Hold For Release