Hiding The Light Of 10 Trillion Suns

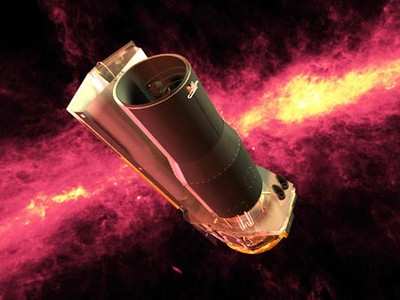

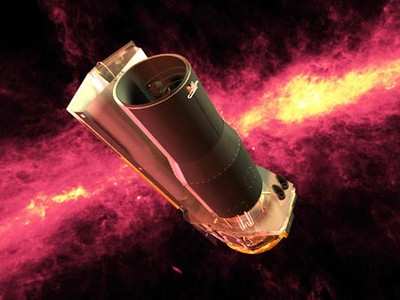

How do you hide something as big and

bright as a galaxy? You smother it in cosmic dust. NASA's Spitzer

Space Telescope saw through such dust to uncover a hidden

population of monstrously bright galaxies approximately 11 billion

light-years away.

How do you hide something as big and

bright as a galaxy? You smother it in cosmic dust. NASA's Spitzer

Space Telescope saw through such dust to uncover a hidden

population of monstrously bright galaxies approximately 11 billion

light-years away.

These strange galaxies are among the most luminous in the

universe, shining with the equivalent light of 10 trillion suns.

But, they are so far away and so drenched in dust, it took

Spitzer's highly sensitive infrared eyes to find them.

"We are seeing galaxies that are essentially invisible," said

Dr. Dan Weedman of Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, co-author of the

study detailing the discovery, published in today's issue of the

Astrophysical Journal Letters. "Past infrared missions hinted at

the presence of similarly dusty galaxies over 20 years ago, but

those galaxies were closer. We had to wait for Spitzer to peer far

enough into the distant universe to find these."

Where is all this dust coming from? The answer is not quite

clear. Dust is churned out by stars, but it is not known how the

dust wound up sprinkled all around the galaxies. Another mystery is

the exceptional brightness of the galaxies. Astronomers speculate

that a new breed of unusually dusty quasars, the most luminous

objects in the universe, may be lurking inside. Quasars are like

giant light bulbs at the centers of galaxies, powered by huge black

holes.

Astronomers would also like to determine whether dusty, bright

galaxies like these eventually evolved into fainter, less murky

ones like our own Milky Way. "It's possible stars like our Sun grew

up in dustier, brighter neighborhoods, but we really don't know. By

studying these galaxies, we'll get a better idea of our own

galaxy's history," said Cornell's Dr. James Houck, lead author of

the study.

The Cornell-led team first scanned a portion of the night sky

for signs of invisible galaxies using an instrument on Spitzer

called the multiband imaging photometer. The team then compared the

thousands of galaxies seen in this infrared data to the deepest

available ground-based optical images of the same region, obtained

by the National Optical Astronomy Observatory Deep Wide-Field

Survey. This led to identification of 31 galaxies that can be seen

only by Spitzer. "This large area took us many months to survey

from the ground," said Dr. Buell Jannuzi, co-principal investigator

for the Deep Wide-Field Survey, "so the dusty galaxies Spitzer

found truly are needles in a cosmic haystack."

Further observations using Spitzer's infrared spectrograph

revealed the presence of silicate dust in 17 of these 31 galaxies.

Silicate dust grains are planetary building blocks like sand, only

smaller. This is the furthest back in time that silicate dust has

been detected around a galaxy. "Finding silicate dust at this very

early epoch is important for understanding when planetary systems

like our own arose in the evolution of galaxies," said Dr. Thomas

Soifer, study co-author, director of the Spitzer Science Center,

Pasadena, CA, and professor of physics at the California Institute

of Technology, also in Pasadena.

This silicate dust also helped astronomers determine how far

away the galaxies are from Earth.

"We can break apart the light from a distant galaxy using a

spectrograph, but only if we see a recognizable signature from a

mineral like silicate, can we figure out the distance to that

galaxy," Soifer said.

In this case, the galaxies were dated back to a time when the

universe was only three billion years old, less than one-quarter of

its present age of 13.5 billion years. Galaxies similar to these in

dustiness, but much closer to Earth, were first hinted at in 1983

via observations made by the joint NASA-European Infrared

Astronomical Satellite. Later, the European Space Agency's Infrared

Space Observatory faintly recorded comparable, nearby objects. It

took Spitzer's improved sensitivity, 100 times greater than past

missions, to finally seek out the dusty galaxies at great

distances.

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.06.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.06.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.06.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.06.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF) ANN FAQ: Q&A 101

ANN FAQ: Q&A 101 Classic Aero-TV: Virtual Reality Painting--PPG Leverages Technology for Training

Classic Aero-TV: Virtual Reality Painting--PPG Leverages Technology for Training Airborne 05.02.25: Joby Crewed Milestone, Diamond Club, Canadian Pilot Insurance

Airborne 05.02.25: Joby Crewed Milestone, Diamond Club, Canadian Pilot Insurance