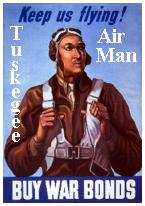

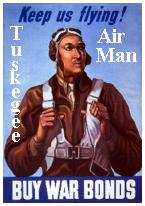

Commemorative Coin Marks Tuskegee Service

Decorated World War II aviator and "Ace" Lee Andrew Archer Jr.,

84, says he dreamed of becoming a fighter pilot at an early

age.

The Yonkers (NY)-born veteran recalled reading comic books

during his boyhood that featured illustrated stories depicting

World War I duels in the skies between Germany's Baron von

Richthofen and allied fliers.

"I wanted to be a pilot," Archer said at a Feb. 19 National

Black History Month commemoration ceremony at Veterans Affairs

Department headquarters, noting that watching planes take off and

land at a small airport near his family's summer home in Saratoga

(NY) also whetted his desire to fly.

A self-described natural competitor, Archer said he pledged to

himself back then that he, too, would one day battle America's

enemies from the cockpit of a fighter plane.

The steely-eyed African-American eventually realized his goal:

he became a member of the US Army Air Corps' famed Tuskegee Airmen

during World War II. During the 169 combat missions he flew in the

European Theater, Archer was credited with downing five enemy

aircraft, earning him the coveted title of "Ace."

Archer, the keynote speaker at the ceremony, noted that about

900 African- Americans were trained to be pilots at a military camp

near Tuskegee College, later renamed Tuskegee University, in

Alabama. Of these service members, he added, 450 saw combat, more

than 60 were killed and 32 were shot down and became prisoners of

war.

The Tuskegee Airmen, he said, flew a

variety of combat missions in Europe, totaling 200, and destroyed

about 500 enemy aircraft and a destroyer. And the Tuskegee Airmen

never lost a bomber to the enemy during allied B-17 and B-24 bomber

formation escort duties, Archer noted.

The Tuskegee Airmen, he said, flew a

variety of combat missions in Europe, totaling 200, and destroyed

about 500 enemy aircraft and a destroyer. And the Tuskegee Airmen

never lost a bomber to the enemy during allied B-17 and B-24 bomber

formation escort duties, Archer noted.

Archer said he was a sophomore at New York University in early

1941 when he decided to enlist in the Army Air Corps to become a

pilot. At the time, however, the US military didn't allow

African-Americans to serve as pilots. And although he passed the

preliminary pilot's test with flying colors, Archer was assigned to

Camp Wheeler (GA) as a communications specialist.

In 1942, the government decided to train a select group of

African-American applicants for military flying duty – a

decision, Archer noted, that was rumored to have been precipitated

by Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of then- President Franklin D.

Roosevelt. Archer said he reapplied for pilot's training and was

accepted, earning his wings in 1943.

Yet, before and after they won their wings, Archer said he and

the other Tuskegee Airmen had to endure the widespread racism that

was prevalent across the US armed forces before President Harry S.

Truman's 1948 order that desegregated America's military.

Archer said that a mid-1920s US War Department study was

responsible for much of the shoddy treatment African-American

service members experienced before Truman's desegregation edict.

That study, he pointed out, essentially said African-Americans

didn't have the intelligence or courage necessary for rigorous

combat duties – even though US African-American combat troops

had fought with documented courage and élan alongside French

forces against the Germans during World War I.

So, although Archer was preeminently qualified to be a fighter

pilot, his coffee-colored skin at first proved to be a hindrance to

his dream.

However, Archer did become an Army

Air Corps pilot, and flew P-40 Tomahawk, P- 39 Air Cobra, P-47

Thunderbolt, and P-51 Mustang fighters during World War II, earning

the rarely awarded Distinguished Flying Cross among numerous other

decorations.

However, Archer did become an Army

Air Corps pilot, and flew P-40 Tomahawk, P- 39 Air Cobra, P-47

Thunderbolt, and P-51 Mustang fighters during World War II, earning

the rarely awarded Distinguished Flying Cross among numerous other

decorations.

The Army Air Corps became the US Air Force in 1947, Archer said,

noting he performed weather squadron hurricane hunting patrols

after World War II and served during the Korean War. He retired as

a lieutenant colonel with 29 years of service in 1970.

Archer left the service for continued success in the civilian

realm as a corporate officer for firms such as General Foods,

Phillip Morris and others, noting he'd also been involved in the

start up of "Essence" magazine and other African-American-owned

enterprises.

The "Tuskegee Experiment," Archer noted, proved that

African-American pilots could fly and fight as well as their white

counterparts and played a key role in Truman's decision to

desegregate the US military, which in turn opened up opportunities

for all African-Americans.

"The country has changed, and it has changed a lot" with regard

to race relations, Archer observed, in part because of the

accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen and other African-American

service members during World War II and of those who followed.

Yet, although race relations across

the military and American society have greatly improved since the

1940s, Archer noted, they still aren't as good as they should be.

But he added that today's generation of African-American military

leaders will continue to build upon the successes of their

predecessors.

Yet, although race relations across

the military and American society have greatly improved since the

1940s, Archer noted, they still aren't as good as they should be.

But he added that today's generation of African-American military

leaders will continue to build upon the successes of their

predecessors.

"This country can be what it is supposed to be, and what it

claims to be," Archer said. "It is in the hands of new troops now,

and I want to wish them luck. I personally see the best for them

and for their country, which is my country, too," he concluded.

(ANN extends a special thanks to Gerry J. Gilmore of the

American Forces Press Service)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.12.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.12.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.12.25): Land And Hold Short Operations

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.12.25): Land And Hold Short Operations ANN FAQ: How Do I Become A News Spy?

ANN FAQ: How Do I Become A News Spy? NTSB Final Report: Cirrus Design Corp SF50

NTSB Final Report: Cirrus Design Corp SF50 Airborne 12.08.25: Samaritans Purse Hijack, FAA Med Relief, China Rocket Fail

Airborne 12.08.25: Samaritans Purse Hijack, FAA Med Relief, China Rocket Fail