Part TWO (of 2) of The EXCLUSIVE ANN

Interview

When last we left Lionel Morrison, he had spent

several "interesting" moments fighting a nearly detached aileron,

an uncommanded roll input and an airplane that threatened to do

strange things with little warning. With that in mind and no

guarantee that a bad situation was not about to become worse, he

maneuvered his beloved SR22 over unpopulated terrain, slowed down

well below the SR22’s 133 kt maneuvering speed, killed the

engine and reached for the "little red handle…"

When last we left Lionel Morrison, he had spent

several "interesting" moments fighting a nearly detached aileron,

an uncommanded roll input and an airplane that threatened to do

strange things with little warning. With that in mind and no

guarantee that a bad situation was not about to become worse, he

maneuvered his beloved SR22 over unpopulated terrain, slowed down

well below the SR22’s 133 kt maneuvering speed, killed the

engine and reached for the "little red handle…"

Lionel figures that it "couldn’t have been

more than" ten minutes that had transpired between the takeoff and

his reach for the CAPS blast handle… "the time is hard for

me to judge… but it wasn’t much."

Lionel figures that it "couldn’t have been

more than" ten minutes that had transpired between the takeoff and

his reach for the CAPS blast handle… "the time is hard for

me to judge… but it wasn’t much."

Lionel remembers that "right after" he recovered control of the

airplane (after the sudden, uncommanded roll), he removed the cover

of the parachute firing mechanism and removed the pin that protects

against accidental discharge.

"I dropped them in the floor or the seat… I don’t

remember… I wasn’t concerned about them any more," he

laughed. "I was ready from then on, but I didn’t want to do

it then… I wanted things, if possible, to be stable and over

open ground."

Morrison spoke about a "certain sense of

trepidation" as he reached to pull the handle, because, you know,

this hadn’t been done before. He related, "Things go through

your head… is this going to work? Is it going to deploy

partially? But… I made my decision that this was what I was

going to do. Fortunately, I had read the manuals again and the

latest CAPS Bulletin and knew the exact procedure for pulling

it… kind of a chin-up position and you keep pulling

it… you don’t pull it a little past the stop, you pull

it a lot… there was a little pause and then you pull it the

rest of the way. And then there seemed another pause and you pull

it some more… all this happens in like half a second -- and

then the rocket actually fired."

Morrison spoke about a "certain sense of

trepidation" as he reached to pull the handle, because, you know,

this hadn’t been done before. He related, "Things go through

your head… is this going to work? Is it going to deploy

partially? But… I made my decision that this was what I was

going to do. Fortunately, I had read the manuals again and the

latest CAPS Bulletin and knew the exact procedure for pulling

it… kind of a chin-up position and you keep pulling

it… you don’t pull it a little past the stop, you pull

it a lot… there was a little pause and then you pull it the

rest of the way. And then there seemed another pause and you pull

it some more… all this happens in like half a second -- and

then the rocket actually fired."

Whoosh

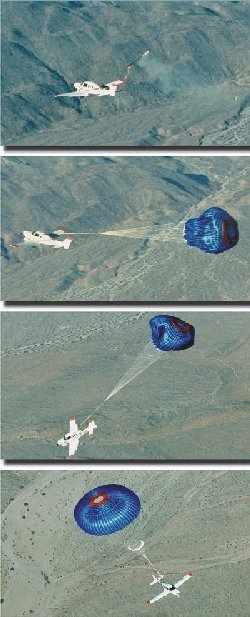

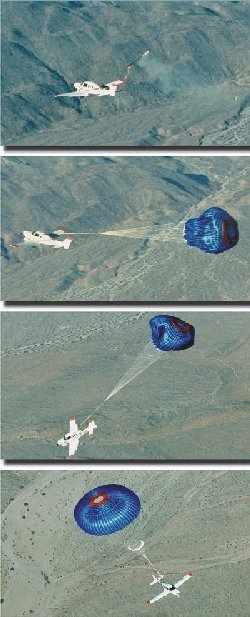

Morrison notes a wealth of sensations when the rocket fired. "It

was, frankly, a big relief. 'All right; so far that part went

right,'" he thought. He wasn't really concerned; it looked

textbook. "I had seen the videos and I knew at the first stages of

the deployment was going to take that nose-down attitude and --

because if you didn’t know that and weren’t frightened

enough already -- that probably would about do you in…

it goes nose-down for a few seconds and than the 'chute deploys

further and you get a pretty violent nose-up attitude until it

settles down… once it does, you're now basically level and

starting a descent."

Cirrus says that, "…to deploy the

parachute, a person must use approximately 35 pounds of pressure

and two separate maneuvers to set off a magnesium charge, which

will ignite a solid-fuel rocket. The rocket will blow out a pop

hatch that covers the compartment in which it is stored. As the

rocket deploys to the rear, the aircraft will slow, and buried

harness straps will unzip from both sides of the airframe." Since

the parachute itself is located behind the baggage compartment,

just forward of the tail, the parachute attachment harness is

faired into recesses in the fuselage structure. They literally

"unzip" during deployment, and the aircraft slowly assumes a final,

more level, attitude within seconds of the firing… hence the

changes that Morrison noted after pulling the blast handle. Within

seconds, the canopy positions itself over the center of gravity of

the aircraft, and descends in a level attitude at about 26.7

ft/sec.

Cirrus says that, "…to deploy the

parachute, a person must use approximately 35 pounds of pressure

and two separate maneuvers to set off a magnesium charge, which

will ignite a solid-fuel rocket. The rocket will blow out a pop

hatch that covers the compartment in which it is stored. As the

rocket deploys to the rear, the aircraft will slow, and buried

harness straps will unzip from both sides of the airframe." Since

the parachute itself is located behind the baggage compartment,

just forward of the tail, the parachute attachment harness is

faired into recesses in the fuselage structure. They literally

"unzip" during deployment, and the aircraft slowly assumes a final,

more level, attitude within seconds of the firing… hence the

changes that Morrison noted after pulling the blast handle. Within

seconds, the canopy positions itself over the center of gravity of

the aircraft, and descends in a level attitude at about 26.7

ft/sec.

A peaceful descent…

With a good canopy over his head, Morrison spoke of the

peacefulness of the moment. "It was a real feeling of serenity," he

remembered. "The descent is very gentle and seems to be very slow,

at least with any kind of altitude. I realized that the 'chutes

deployed, I’m descending safely, I was getting rather close

to some high power lines and I was a little concerned about it --

but, you know, I couldn’t do anything about it, either -- but

it quickly became clear that I wasn’t going to hit those so

that worry was gone. One concern I did have was that I had no sense

of how far I would drift once I deployed the chute; I was over this

clear area that wasn’t THAT big and I was worried about

drifting away from it. I had gone to the far edge of the clear area

into the wind where I would have more of the clear area underneath

me… but it was, still a big question mark. I really wish I

knew how far I did drift but I expect it wasn’t actually, all

that far."

Morrison continued, "I do remember looking down, and at about

100 feet or so, watching the ground start coming up REAL fast. I

just sat back in the seat, pulled the seat belt again as tight as I

could and got my feet out from under me and braced for the impact

-- which turned out to be pretty hard."

Morrison kept going: "My impact, I think, was different from

what was designed for this system. I know the landing gear is

designed to absorb a lot of the energy [during the impact], but my

landing gear, I don’t think they absorbed all that much of

the energy because I hit those little trees… In the

pictures, it looks like I’m up in the treetops, but those

trees are very small -- they’re just cedar and mesquite. When

the plane came to rest, I was probably about four feet off the

ground. But the wings took much of the force, not the gear. As we

hit the trees, the plane nosed, took out one blade of the prop

(which buried itself in the ground); and the nose wheel took some

damage, as well."

It's the sudden stop…

That last bit of the impact was the most violent,

the lurch forward as Morrison, SR22 and company slid forward and

nosed in. "I took a pretty big impact on the nose of the airplane.

Which is the only thing that caused me any significant discomfort

all… even though I’m strapped real tight to the seat,

when the plane pitched forward like that, my neck went with it. I

felt some pain in my neck which is now completely gone away. I

expected a stiff neck the next day but I didn’t [experience

it]. I think that if I hit in a more flat attitude on the mains, I

don’t think I’d probably have had even the neck

situation."

That last bit of the impact was the most violent,

the lurch forward as Morrison, SR22 and company slid forward and

nosed in. "I took a pretty big impact on the nose of the airplane.

Which is the only thing that caused me any significant discomfort

all… even though I’m strapped real tight to the seat,

when the plane pitched forward like that, my neck went with it. I

felt some pain in my neck which is now completely gone away. I

expected a stiff neck the next day but I didn’t [experience

it]. I think that if I hit in a more flat attitude on the mains, I

don’t think I’d probably have had even the neck

situation."

Very Little Damage

Lionel couldn't believe it, when he had a good look at his

"wreck." He said, "…and my airplane is hardly damaged at

all! Most of the apparent damage was done when the straps ripped

off the fuselage skin when the chute deployed. One prop blade is

bent in the middle."

As the dust settled [literally, Morrison enjoyed a

split second of self-congratulatory survival feelings but quickly

evacuated the aircraft], "I was on the ground, unbelievably

relieved; I was safe; my adrenalin level was off the chart and I

gathered some stuff, climbed out of the aircraft." Despite the fact

that the aircraft was half-fueled, there was no fire, and, from

looking around him, Morrison did not feel fire was imminent; but

nevertheless he got out of the aircraft and onto the ground

quickly. Morrison then faced one of the greatest hazards he had

faced all day: "Mesquite trees have these big thorns on

them… and I gingerly had to get off the airplane because I

was trying to avoid the mesquite thorns."

As the dust settled [literally, Morrison enjoyed a

split second of self-congratulatory survival feelings but quickly

evacuated the aircraft], "I was on the ground, unbelievably

relieved; I was safe; my adrenalin level was off the chart and I

gathered some stuff, climbed out of the aircraft." Despite the fact

that the aircraft was half-fueled, there was no fire, and, from

looking around him, Morrison did not feel fire was imminent; but

nevertheless he got out of the aircraft and onto the ground

quickly. Morrison then faced one of the greatest hazards he had

faced all day: "Mesquite trees have these big thorns on

them… and I gingerly had to get off the airplane because I

was trying to avoid the mesquite thorns."

The peace didn't last long, as 'celebrity' set in…

Morrison was amazed at how quickly people showed up on the

scene… and laughed about questions local golfers (he landed

on a golf course) asked him if he had “aimed for the

course… as if I could aim this thing,” Morrison

laughed. He also noted that in typical golfer fashion, once his

safety was assured, the golfers said they were glad he was OK and

said they that had to get back to their game… "I’m

also a golfer… so I totally understood," Morrison added.

The police and fire departments followed in short

order. Local construction guys cleared a swath through the veggies

with a few bulldozers so that they could get access to the

aircraft. Morrison waited on the scene, waiting for the NTSB

(because the police told him he had to). Lionel also admitted that

he avoided the media while waiting this matter out because he was

"afraid I might say something stupid and I didn’t want to

take the risk."

The police and fire departments followed in short

order. Local construction guys cleared a swath through the veggies

with a few bulldozers so that they could get access to the

aircraft. Morrison waited on the scene, waiting for the NTSB

(because the police told him he had to). Lionel also admitted that

he avoided the media while waiting this matter out because he was

"afraid I might say something stupid and I didn’t want to

take the risk."

The Fire chief eventually gave him permission to leave, and he

got a ride home from one of the witnesses, where he spent the next

day with the folks of Cirrus, BRS, FAA and NTSB; and then promptly

went fishing…

How were they biting? "I did great," Morrison said. "You coulda

caught 'em with a safety pin on a string… it was great."

And, now?

Morrison looks back at this, several days later, quite calmly

and objectively. "People asked me if I was freaked out and I can

honestly 'NO.' I mean, what good would that do? You have to figure

out the situation, so you’re so occupied with trying to do

that that you don’t really have time to deal with that

[getting freaked out]." However, "I will tell ya that the last time

I looked out the window I realized I wasn't going all that slow

anymore and my opinion of my descent rate changed real quickly. I

realized that this was going to be a jolt -- and it was."

He's happy.

"I think it’s wonderful that the system

works and that the system has been vindicated; and while I would

happily have preferred to have NOT been the one to try this, I

think this will help other pilots who have this worry about whether

the system will work. That’s, for the most part, gone now, I

think. And I think that’s a great thing," Mr. Survivor

said.

"I think it’s wonderful that the system

works and that the system has been vindicated; and while I would

happily have preferred to have NOT been the one to try this, I

think this will help other pilots who have this worry about whether

the system will work. That’s, for the most part, gone now, I

think. And I think that’s a great thing," Mr. Survivor

said.

Get back on the horse?

What’s next for Morrison (pictured right)? He’s not

totally sure right now, but he’s "95% sure" he’ll fly

again (the whole import of last week is just sinking in) and if he

does, it’ll be in a Cirrus. "From an intellectual standpoint,

it only makes sense to keep flying because its not like the

situation was a total surprise… you have to prepare for

these things no matter what form they come in and I had a good

airplane with a great backup system and it worked… so I have

MORE confidence now, not less confidence… I think I’ll

continue (to fly)."

A Few Notes: ANN’s Editor-In-Chief, Jim

Campbell, a highly-experienced test pilot, conducted this

interview… and was in a unique position to talk to Morrison,

because he had done three aircraft/parachute test drops, under a

BRS or Handbury canopy, in the 1980s, while testing the Cessna

systems then being developed by both companies (although

Handbury’s would never see completion, as Mr Handbury died in

a tragic but unrelated aircraft accident). Interestingly, Campbell

had also deployed a BRS system, "in anger," several years ago, on a

small ultralight air vehicle when it developed a control failure

and a proper landing was obviously not in the cards. Obviously,

Morrison and Campbell got on quite well with this shared experience

between them.

Campbell is effusive in his praise for Morrison.

"Despite all my experience in flight test, I have to say that

I’d be hard-pressed to do a better job than that done by

Morrison… his thought processes were dead-on, his reasoning

impeccable, and his ultimate decision to use the 'chute because he

did not know if his current condition was to get worse is simply

unimpeachable, in my opinion. I not only concur with how he seems

to have handled himself, I strongly doubt I could have improved on

his performance. [Listen, folks: if Campbell says this, you KNOW

he's impressed --ed.] Morrison was (obviously) VERY well trained,

and possessed an excellent attitude toward his aircraft and the

hazards he might have to deal with. I’m tremendously

impressed with him and found him to be a pretty cool fellow."

Campbell is effusive in his praise for Morrison.

"Despite all my experience in flight test, I have to say that

I’d be hard-pressed to do a better job than that done by

Morrison… his thought processes were dead-on, his reasoning

impeccable, and his ultimate decision to use the 'chute because he

did not know if his current condition was to get worse is simply

unimpeachable, in my opinion. I not only concur with how he seems

to have handled himself, I strongly doubt I could have improved on

his performance. [Listen, folks: if Campbell says this, you KNOW

he's impressed --ed.] Morrison was (obviously) VERY well trained,

and possessed an excellent attitude toward his aircraft and the

hazards he might have to deal with. I’m tremendously

impressed with him and found him to be a pretty cool fellow."

Campbell concluded, "Further, I hope that this incident gets a

lot of play in the regular media… because if the public gets

to see Mr. Morrison as representative of the typical low-time GA

pilot, we’re all going to come off looking quite positively.

He did us all proud."

Related Stories:

NTSB Prelim: Sikorsky UH60 Sikorsky UH-60

NTSB Prelim: Sikorsky UH60 Sikorsky UH-60 Aero-News: Quote of the Day (11.13.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (11.13.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (11.13.25): Ground Clutter

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (11.13.25): Ground Clutter ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (11.13.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (11.13.25) Airborne 11.07.25: Affordable Expo Starts!, Duffy Worries, Isaacman!

Airborne 11.07.25: Affordable Expo Starts!, Duffy Worries, Isaacman!