Columbia Investigation Focuses on Problems At

NASA

The investigation into what caused the tragic

demise of the Space Shuttle Columbia plods along, with one

member of the board feeling a touch of deja vu. Dr. Sally Ride,

America's first woman in space, was a member of the

Challenger investigation board in 1986. Now, she's on the

board investigating Columbia's destruction as it

re-entered the atmosphere on Feb. 1.

The investigation into what caused the tragic

demise of the Space Shuttle Columbia plods along, with one

member of the board feeling a touch of deja vu. Dr. Sally Ride,

America's first woman in space, was a member of the

Challenger investigation board in 1986. Now, she's on the

board investigating Columbia's destruction as it

re-entered the atmosphere on Feb. 1.

Ride said she's hearing what sounds a lot like what she heard 17

years ago: Serious problems with a particular component or

components, repeatedly weathered by various shuttle missions, might

have catastrophically failed because management misread the threats

as maintenance headaches.

Is There An Echo In Here?

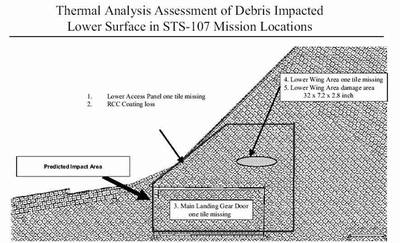

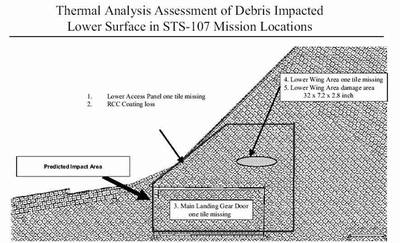

In 1986 it was leaky O-rings on solid fuel booster rockets; this

time, it seemed, debris — perhaps the shuttle's own foam

insulation — might have dealt the craft a fatal blow.

Another authority who drew similar parallels was Prof. Diane

Vaughan of Boston College, whose scholarly review of the 1986

disaster in her book, "The Challenger Launch Decision:

Risky Technology, Culture and Deviance at NASA," earned her a

platform as an expert witness in the Columbia case.

Professor Vaughan, a sociologist who is to testify this month, said

in an interview that the similarities became obvious to her in

early February, in reports that mentioned longstanding problems

with falling foam and the shuttles' fragile insulating tiles.

Another authority who drew similar parallels was Prof. Diane

Vaughan of Boston College, whose scholarly review of the 1986

disaster in her book, "The Challenger Launch Decision:

Risky Technology, Culture and Deviance at NASA," earned her a

platform as an expert witness in the Columbia case.

Professor Vaughan, a sociologist who is to testify this month, said

in an interview that the similarities became obvious to her in

early February, in reports that mentioned longstanding problems

with falling foam and the shuttles' fragile insulating tiles.

She then watched NASA officials like the Columbia

program manager, Ron D. Dittemore, explain at news conferences that

the National Aeronautics and Space Administration had decided the

occasional damage from dislodged foam and other liftoff debris was

a risk NASA had grown comfortable with. To Professor Vaughan, Mr.

Dittemore's assessment seemed evidence of something all too

familiar: NASA management's "incremental descent into poor

judgment."

Dr. Vaughn said she did not think that in either

accident people had necessarily done their jobs improperly or had

violated NASA procedures. Instead, Ms. Vaughan said she saw a

flawed culture in which most participants gradually demoted their

concerns, causing major problems to be pushed off as lower-level

issues.

Dr. Vaughn said she did not think that in either

accident people had necessarily done their jobs improperly or had

violated NASA procedures. Instead, Ms. Vaughan said she saw a

flawed culture in which most participants gradually demoted their

concerns, causing major problems to be pushed off as lower-level

issues.

As she wrote of Challenger workers in her book:

"Following rules, doing their jobs, they made a mistake. With all

procedural systems for risk assessment in place, they made a

disastrous decision."

Vaughan maintains the true error resided in the system. Once

officials in the rocket booster program, including Lawrence Mulloy,

the project leader, left NASA, the problem was treated as

solved.

But Was It?

"That need to make individuals accountable can

backfire, because once individuals are shifted out of their

positions and the personnel are changed, it looks as if all of the

problems have been cleared up," Professor Vaughan said. "That means

that the organizational problems that shaped their decision making

go unchecked."

"That need to make individuals accountable can

backfire, because once individuals are shifted out of their

positions and the personnel are changed, it looks as if all of the

problems have been cleared up," Professor Vaughan said. "That means

that the organizational problems that shaped their decision making

go unchecked."

In NASA's case, she said, one such problem is budgetary. In her

opinion the agency does not have enough money to do its job over

the long run without cutting corners.

"You have to look beyond individuals and look to the situation

in which they work," Professor Vaughan added. "Otherwise you're

just going to reproduce the problem. And that's what's happened

— again."

Mulloy: "Challenger Scapegoat"

Mulloy, who has retired, says he was made a scapegoat. "That was

their primary focus in 1986, to find somebody to put the public

face on for blame," he said, "and I was the lucky nominee for

that."

Whatever the physical cause of the Columbia accident is

determined to be, it is clear that the space agency's decision

making culture has become as important to the board as any falling

foam or data recorder.

"We need to have the aperture of our focus opened

up to see things the way she sees them," Adm. Harold W. Gehman Jr.,

chairman of the investigation board, said this week of Professor

Vaughan.

"We need to have the aperture of our focus opened

up to see things the way she sees them," Adm. Harold W. Gehman Jr.,

chairman of the investigation board, said this week of Professor

Vaughan.

At the hearings this week, the admiral sounded a lot like her.

"We have not concluded that the analysis and the decision making

was wrong," Admiral Gehman said. "They may have done everything

they could with the information that they had available. They may

have had all the right people in the room, and asked all the right

questions, and considered all the right factors, and just come up

with the wrong answer."

After the hearings, he explained why the board was taking this

approach. "We have to have a better working theory than hindsight,"

he said. The no-fault approach bothers some at NASA, who say they

think determining responsibility for mistakes is important.

Professor Vaughan agrees that individual responsibility is

important. But she draws a distinction between assigning

responsibility and scapegoating, which she maintains does not fix

the deeper problem. "You change the cast of characters, and you

don't change the organizational context," she said. "And the new

person can be under the same constraints and conditions that they

were under before."

The board is still gathering and reviewing debris and data,

digesting the discoveries it has made about NASA's responses to the

blow from the foam chunk that occurred about 80 seconds into the

Columbia's flight.

Software Misused?

The board has discovered that the software used by Boeing, a

NASA contractor, to evaluate the damage had never been used during

a mission before and was not designed as a predictive tool. In

fact, it was little more than an Excel spreadsheet that described

past strikes and damage.

Professor Vaughan, looking at the chain of events now, said that

the seemingly hard numbers of the Boeing analysis appeared at the

time to trump the gut feelings of the engineers. Admiral Gehman has

said the board probably will not write its final report until June.

But its charter, written by NASA, calls only for recommendations to

improve safety and return to flight — in other words,

prevention, not punishment.

That is the standard model for aviation and military "mishap

investigations," like the one after the terrorist attack on the

destroyer Cole in Yemen in October 2000. That inquiry was also

conducted by Admiral Gehman.

But it remains to be seen whether this approach can break what

Mulloy, for one, fears may be a pattern at NASA.

"The mistake in judgment we all made was accepting deviance in

the performance from the hardware from what it was designed to do,"

Mr. Mulloy said of events before the Challenger disaster.

Once the erosion in O-rings was tested and analyzed and accepted,

"we started down the road to the inevitable accident.

"If — and this is a big if, with big capital letters in

red — if the cause of the Columbia accident is the

acceptance of debris falling off the tank in ascent, and impacting

on the orbiter, and causing damage to the tiles — if that

turns out to be the cause of the accident, then the lesson we

learned in Challenger is forgotten, if it was ever

learned."

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (10.27.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (10.27.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.27.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.27.25) NTSB Prelim: Lancair 320

NTSB Prelim: Lancair 320 Airborne Programming Continues Serving SportAv With 'Airborne-Affordable Flyers'

Airborne Programming Continues Serving SportAv With 'Airborne-Affordable Flyers' Airborne-Flight Training 10.23.25: PanAm Back?, Spirit Cuts, Affordable Expo

Airborne-Flight Training 10.23.25: PanAm Back?, Spirit Cuts, Affordable Expo