Attorneys Argued That Skymaster Was Improperly Maintained,

Leading To The Crash

One of the largest verdicts resulting from an airplane accident

was handed down on December 14 by a Philadelphia jury. Dr. Robert

Marisco Jr. and his fiancee Heather Moran, both of Akron, Ohio,

were awarded $11.35 million in compensatory damages in an action

against Winner Aviation Corporation, a repair facility based at

Youngstown-Warren Regional Airport in Ohio.

Dr. Marisco, a dermatologic surgeon, and Ms. Moran, the pilot,

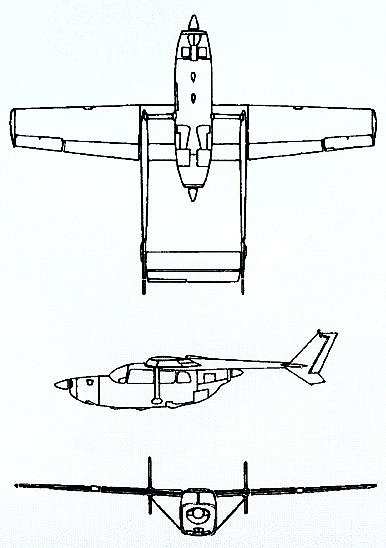

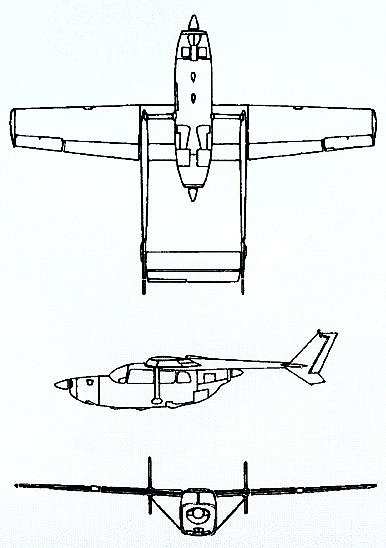

were flying back to Ohio in Dr. Marsico's Cessna 337 when it

developed an engine problems and went down about 10 miles from

DeKalb-Peachtree Airport in Georgia on Aug. 8, 2007. A post-crash

fire ensued. Dr. Marisco and Ms. Moran both suffered multiple

injuries, including third degree burns covering nearly 40 percent

of their bodies.

The NTSB notes in its probable cause report that "the pilot, age

34, held a commercial pilot certificate with airplane single engine

land, multi engine land, and instrument airplane ratings, and a

CL-65 rating with "SIC privileges only." The pilot reported 4,650

hours of total flight time, with 145 hours in make and model. Her

latest FAA first class medical certificate was issued on June 5,

2007."

At trial, attorneys for the plaintiffs said Dr. Marsico's Skymaster

had been maintained by Winner Aviation prior to his acquisition of

the aircraft, and he continued that relationship after he purchased

it in 2006. According to the attorneys, from 2006 until the time of

the crash, the Skymaster had reportedly experienced recurrent

problems with its rear engine. Winner Aviation performed repeated

troubleshooting on a waste gate. On the day of the crash, the rear

engine on the twin-engine airplane lost power after takeoff, and

attempts to restart it failed. Ms. Moran was unable to maintain

altitude and attempted an emergency landing. A post-crash fire

ensued.

At trial, plaintiffs claimed, among other things, that Winner

Aviation did not maintain the aircraft in an "airworthy condition."

Plaintiffs further alleged that Winner Aviation's misdiagnosis of

the recurrent problems of "power loss" in the rear engine was

compounded by an alleged failure to have an appropriate inspector

investigate all work that was being performed by its mechanics.

Plaintiffs also alleged that Winner Aviation was aware that the

front engine was long overdue for a complete overhaul, but did not

recommend an overhaul to Dr. Marsico. Plaintiffs argued at trial

that the failure to overhaul this engine or, at the very least,

perform a proper inspection and repair of its valve guides and

other engine parts, caused a diminution of power during an

in-flight emergency—precisely when full power was most

important.

The NTSB probable cause report, which is not admissible as

evidence in court, confirmed the engine failure but placed the

responsibility for the accident with the pilot. According to the

report, "Shortly after takeoff on a hot day, after the airplane was

about 10 miles from the departure airport, the rear engine failed

for undetermined reasons. The pilot turned the airplane back toward

the airport, feathered the rear engine, and maintained front engine

power at the top of the green arc of the manifold pressure gage, at

33 inches of manifold pressure. The airplane did not maintain

altitude at that power setting, and to avoid houses and vehicles on

the ground, the pilot performed a forced landing at a water

treatment plant. During the landing, the airplane struck the top of

a concrete structure, hit the ground, and became engulfed in

flames. According to the owner’s manual, after an engine

failure, the remaining engine power to be used is to be "increased

as required." The published maximum power setting was 37 inches of

manifold pressure at "red line," without any time limitations. A

performance calculation indicated that at the existing ambient

temperatures, and at that power setting, the airplane should have

climbed at least 290 feet per minute. Additional references to the

use of a 37-inch power setting, including performance calculations,

were noted in the owner’s manual."

The report also states that "At the time of the engine failure,

the pilot estimated the airplane was 1,000 to 1,500 feet above the

ground, and between 2,700 feet and 3,000 feet above mean sea level

(msl). GPS indicated a small airport about 6 miles away, but the

pilot felt the larger airport they had just departed, about 10

miles to the south, would be better due to emergency equipment and

a control tower. The pilot then began a gradual turn back toward

the south, and while doing so, asked the passenger to verify rear

engine switch positions. She then attempted an engine restart, and

when it was unsuccessful, she contacted DeKalb-Peachtree Tower and

advised the controller of the situation."

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable

cause(s) of this accident to be the "pilot’s failure to

utilize all of the power available following an engine failure.

Contributing to the accident were the failure of the rear engine

for undetermined reasons."

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.27.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.27.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.27.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.27.25) Classic Aero-TV: Veteran's Airlift Command -- Serving Those Who Served

Classic Aero-TV: Veteran's Airlift Command -- Serving Those Who Served Airborne-NextGen 04.22.25: NYC eVTOL Network, ForgeStar-1, Drone Safety Day

Airborne-NextGen 04.22.25: NYC eVTOL Network, ForgeStar-1, Drone Safety Day Airborne 04.21.25: Charter Bust, VeriJet Woes, Visual Approach Risks

Airborne 04.21.25: Charter Bust, VeriJet Woes, Visual Approach Risks