Rosetta Spacecraft 'Spoiled' With Possible Options

It's something that has never been done before; a mission team selecting a landing site on a comet. But soon, the Philae lander will be the first spacecraft ever to land on a comet and conduct in situ measurements.

The ESA Rosetta spacecraft and the Philae lander began their journey to their final destination – comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko – 10 years ago. As the spacecraft approach their target, the task of the lander team, which is led by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), has not been easy. The comet's surface is not just made up of flat areas, but features numerous crevasses, slopes, craters and boulders. "Based on the particular shape and the global topography of Comet 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko, it is probably no surprise that many locations had to be ruled out," says DLR researcher Stephan Ulamec, Project Manager for the Philae lander. On August 24, five possible landing sites were finalized. "The candidate sites that we want to follow up for further analysis are thought to be technically feasible on the basis of a preliminary analysis of flight dynamics and other key issues – for example they all provide at least six hours of daylight

per comet rotation and offer some flat terrain."

During the selection process, the scientists from the DLR Lander Control Center in Cologne, the Science, Operations and Navigation Center (SONC) of the French space agency, CNES, together with the scientists who are operating instruments on board Philae, took into account various criteria – for example, plenty of solar illumination is required to charge Philae's batteries after the first 64-hour scientific phase, so that it operates for a long period of time and is able to conduct additional science investigations. If the lander does not receive sufficient energy, there will be consequences for the planned 'long term science phase', the phase in which all instruments will be studying the evolution of the comet on its path towards the Sun. Permanent sunlight would, in contrast, cause the lander to overheat, thus limiting the operational life of Philae and its instruments. The time that passes between the separation of the lander from the mother craft to the actual landing will have an impact on

the science – the longer it takes to land, the lower the amount of energy that will be available for the first science phase on the comet's surface.

The landing could be risky if the terrain is too rugged and there are, for example, depressions and boulders the size of the lander or steep slopes in the area. Since the position of the Rosetta orbiter when it releases Philae toward the comet cannot be determined precisely, scientists can define a landing ellipse with a diameter of about one kilometre. If the lander misses the targeted area, it could touch down in the adjoining region, perhaps encountering a rather unfriendly environment. The selected landing site must also allow regular communications between the Rosetta orbiter and the lander, to send the acquired data back to Earth. Only then will the wishes of the scientists be taken into account; they would prefer to select a possibly active, off-gassing, but also primordial region, in which the cometary material has barely changed since the formation of the Solar System 4.5 billion years ago.

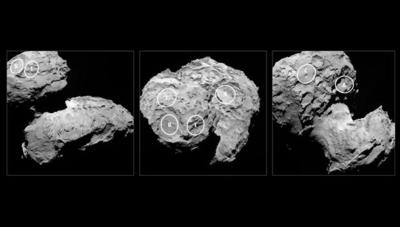

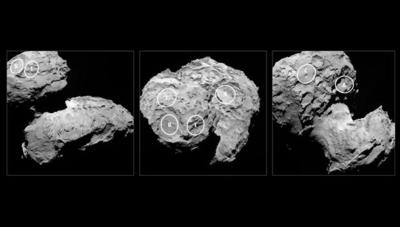

However, the ideal landing site – one with a flat surface, plenty of hours of sunlight, good accessibility and ensuring optimal scientific conditions – has not been discovered on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko by the lander team. During the selection process, they had to weigh the pros and cons and swallow several bitter pills. "It is clear that we have to compromise," says Ulamec. The first data regarding temperatures, outgassing and terrain has been produced by instruments on the orbiter. From the first 10 possible landing sites, A to H, the lander team finally chose five candidates on the comet, which consists of a smaller lobe, a larger lobe and a narrow, very active 'neck' connecting them together. Three of the possible landing sites (B, I and J) are located on the lower section of the comet and the remaining two (A and C) are found on the larger part of the cometary body.

"Every site has the potential for unique scientific discoveries," says Ulamec. The DLR Institute of Planetary Research has a leading role in four scientific instruments on the mission and is involved in three other experiments. The ROLIS (Rosetta Lander Imaging System), located on the bottom of the lander will, during the descent, already begin to acquire its first images of the comet. Then, it will examine the surface structure of the comet. The thermal probe MUPUS (Multi-Purpose Sensors for Monitoring Experiment) will penetrate up to 40 centimetres into the comet to measure the temperature and thermal conductivity. The SESAME experiment is mounted in the soles of the lander feet and transmits and receives acoustic and electric signals.

These tools will only be able to be used if Philae lands safely. Until September 14, the lander team will therefore take a closer look at the five possible candidate sites and choose two finalists. In October, after more detailed analyses, the final landing site will be determined. The much anticipated moment is scheduled to occur on November 11 – the first ever landing on a comet and the first scientific investigations conducted on a comet's surface.

(Image provided by DLR)

NTSB Final Report: Cozy Cub

NTSB Final Report: Cozy Cub ANN FAQ: Contributing To Aero-TV

ANN FAQ: Contributing To Aero-TV Classic Aero-TV: Seated On The Edge Of Forever -- A PPC's Bird's Eye View

Classic Aero-TV: Seated On The Edge Of Forever -- A PPC's Bird's Eye View ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.29.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.29.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.29.25): Execute Missed Approach

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.29.25): Execute Missed Approach