Author Of "2001: A Space Odyssey" Was 90

by ANN Managing Editor Rob Finfrock

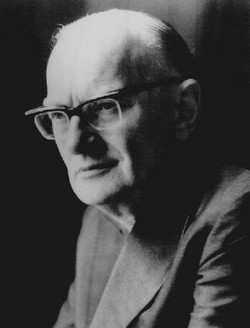

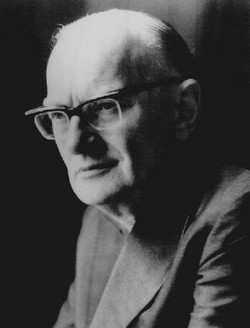

He was more than "just" a

writer of science fiction tales. Arthur C. Clarke was a visionary

-- the true embodiment, in fact, of that term so often applied

to many within the aerospace field. On Wednesday, Clarke

passed away in his adopted home of Sri Lanka at the age of 90,

following a decades-long battle with post-polio syndrome.

He was more than "just" a

writer of science fiction tales. Arthur C. Clarke was a visionary

-- the true embodiment, in fact, of that term so often applied

to many within the aerospace field. On Wednesday, Clarke

passed away in his adopted home of Sri Lanka at the age of 90,

following a decades-long battle with post-polio syndrome.

While he wrote a number of short stories and books -- including

"The Sentinel," "Childhood's End," "The City and The Stars," and

"Rendezvous with Rama" -- Clarke is best known to the masses as the

author of "2001: A Space Odyssey," the novelization of the movie by

the same name. Clarke wrote the book while working on the

screenplay of the classic 1968 sci-fi film with Stanley

Kubrick.

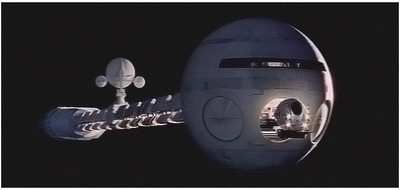

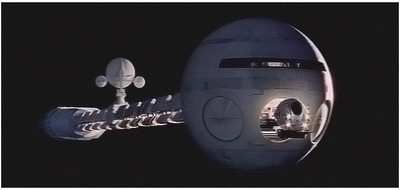

"2001" wasn't a film you went to the theater to watch idly, just

to be entertained; those who did were likely shocked at what they

saw. From the moment the haunting "Also sprach Zarathustra" played

over the speakers... to the eerie (and, as Clarke would often point

out, scientifically accurate) silence accompanying images of a

rotating space station over Earth, or a slender interplanetary

spaceship making its way to Saturn (Jupiter in the book) to meet

the mysterious monolith... to Dave Bowman's last, breathless gasp

"My God, it's full of stars!"... many people soon realized

they weren't just watching a science-fiction tale; they were

witnessing an allegorical history of the entire human race. (Those

who didn't probably walked out early, scratching their heads.)

"2001" was also an exploration of a number of issues Clarke had

visited upon in his earlier works. The dangers of technology, for

one... whether it be embodied in a bone used as a weapon, or as a

considerate, though manic, computer. Others saw the religious

overtones of the monolith that witnessed The Dawn of Man; still

more saw references to Greek epics -- most obviously Homer's

"Odyssey," but on the even-grander scale of space.

Granted, Clarke's timeframe was off... though in 1968, a year

before the Apollo moon landing, it perhaps wasn't too hard

to imagine such accomplishments in just 33 years' time. More

importantly, Clarke also predicted a number of technological and

scientific advancements... often, with frightening accuracy. "2001"

foresaw the advent of glass-panel instrument decks in spaceships...

artificial intelligence... and a vast, orbiting space station that

today's ISS will never come close to approximating, but exists in a

similar spirit of global cooperation.

"2001 was written in an age which now lies beyond one of the

great divides in human history; we are sundered from it forever by

the moment when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped out on to

the Sea of Tranquility," Clarke wrote on the 20th anniversary of

the Apollo 11 moon landing, in 1989. "Now history and fiction have

become inexorably intertwined."

It wasn't the first, or last, time Clarke would make such

accurate predictions. In 1945, Clarke wrote a memo about global

communications satellites... 17 years before they truly became a

reality with the first TelStar satellites. In his works following

"2001," Clarke described the concept of aerobraking... a method of

orbital entry used today to slow down probes visiting Mars.

Those are but a few examples.

At his peak, Clarke published three books a year. He published

the best-selling "3001: The Final Odyssey" -- the fourth and last

in the series began with "2001" -- at the age of 79, according to

The Associated Press. He also wrote non-fiction items on space

travel, and of his research of the Great Barrier Reef and Indian

Ocean.

Clarke won numerous awards, of course. He took home the Science

Fiction Writers of America's Nebula Award three times in the 1970s,

and the Hugo Award of the World Science Fiction Convention twice.

Clarke was also named an honorary fellow by the American Institute

of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Near the end, Clarke said he

wished for three things -- for the world to embrace non-polluting

sources of energy, an end to Sri Lanka's ongoing civil war, and for

evidence of extraterrestrial beings to be finally discovered.

Near the end, Clarke said he

wished for three things -- for the world to embrace non-polluting

sources of energy, an end to Sri Lanka's ongoing civil war, and for

evidence of extraterrestrial beings to be finally discovered.

"Sometimes I am asked how I would like to be remembered," Clarke

said recently. "I have had a diverse career as a writer, underwater

explorer and space promoter. Of all these I would like to be

remembered as a writer."

He also held onto a biting sense of humor. In an AP interview,

Clarke said he didn't regret never himself traveling into space...

since he'd arranged to have DNA from his hair to be sent into

orbit. "One day, some super civilization may encounter this relic

from the vanished species and I may exist in another time," he

said. "Move over, Stephen King."

With that in mind, I think Clarke would appreciate the fact

there's a tune I haven't been able to get out of my head, since I

first read of Clarke's passing three hours ago. Its title -- "Daisy

Bell" -- isn't as well-known as the lyrics, sang by the HAL 9000

computer onboard Discovery One as it lapsed into

unconsciousness.

"Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do..."

A legend has passed... as we all inevitably do, legend or no.

But Arthur C. Clarke's ideas and ideals will truly live

forever.

NTSB Final Report: Cozy Cub

NTSB Final Report: Cozy Cub ANN FAQ: Contributing To Aero-TV

ANN FAQ: Contributing To Aero-TV Classic Aero-TV: Seated On The Edge Of Forever -- A PPC's Bird's Eye View

Classic Aero-TV: Seated On The Edge Of Forever -- A PPC's Bird's Eye View ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.29.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.29.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.29.25): Execute Missed Approach

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.29.25): Execute Missed Approach