ANN's Exclusive Interview With Eclipse CEO Vern Raburn

"Last year at Oshkosh," Eclipse CEO Vern

Raburn began, "we fully intended to fly on the first day of the

convention. We were bringing in a Jumbotron, and we were going to

'broadcast' the first flight, at the show."

"Last year at Oshkosh," Eclipse CEO Vern

Raburn began, "we fully intended to fly on the first day of the

convention. We were bringing in a Jumbotron, and we were going to

'broadcast' the first flight, at the show."

"We're nothing if not aggressive," he noted; but, as the little

things that always crop up, cropped up, he didn't get that

broadcast going. "...but we're not stupid." What happened? "We were

ready... Williams was anything but." Eclipse had held its rollout

celebration just days earlier, and it was, um, 'close.' They had

planned to bring the airplane out under its own power, but "just

one was working." The roll-out was made without the engine

noise.

On August 26, 2002, the

Eclipse 500 made its first flight (right). "The NBAA convention

[held immediately thereafter] was wonderful." There were problems,

though. Eclipse was not impressed by the performance of the

Williams EJ22.

On August 26, 2002, the

Eclipse 500 made its first flight (right). "The NBAA convention

[held immediately thereafter] was wonderful." There were problems,

though. Eclipse was not impressed by the performance of the

Williams EJ22.

"Three days after that flight, Williams came in to the factory

with a 5-hour presentation: 'Here's how we're going to solve all

the problems,' they said." Raburn told us that was the first time

they had acknowledged that the problems even existed.

Time's A-wasting.

"We were supposed to have certified engines in May of this year,

for us to get the airplane certified by December," Raburn said. "In

October 2002, they announced -- they didn't confer with us -- that

they would slip certification to November." Why didn't Raburn cut

and run at that time? "We were still committed -- we had spent

millions. We were profoundly troubled, and we were concerned about

those engines. We said so at NBAA."

Things hadn't gone well

in Walled Lake (MI), Williams' HQ. "By October 1, Williams had

tested about half their 'fixes' -- and not one of them

worked," Raburn said. "They tested in non-real-world

conditions. For instance, they would blow-start the engines. The

starters we got would fail after about every 25 starts. We finally

rigged up a bucket of ice to run tubing through, to blow

refrigerated air through the starters." Williams, too, had been

aggressive in their delivery program, trying two novel starters,

neither of which, Mr. Raburn said, worked very well.

Things hadn't gone well

in Walled Lake (MI), Williams' HQ. "By October 1, Williams had

tested about half their 'fixes' -- and not one of them

worked," Raburn said. "They tested in non-real-world

conditions. For instance, they would blow-start the engines. The

starters we got would fail after about every 25 starts. We finally

rigged up a bucket of ice to run tubing through, to blow

refrigerated air through the starters." Williams, too, had been

aggressive in their delivery program, trying two novel starters,

neither of which, Mr. Raburn said, worked very well.

Eclipse developed a self-start module which didn't work too

well, either, Raburn noted.

Eventually, he said, "They went to a conventional starter that

was built for 400 amps, and pumped 600 amps through it."

So, Vern said, "by

mid-October of last year, we realized that the engine was just too

delicate. We weren't ready to accept their two standard

positions:

So, Vern said, "by

mid-October of last year, we realized that the engine was just too

delicate. We weren't ready to accept their two standard

positions:

- yes, there is a problem; send money; or

- we have it fixed, but there's no guarantee."

Indignation was the next phase.

The clock was running, and Raburn said patience was wearing

thin. "They [Williams] were offended that we questioned anything

they were doing -- everything, to them, was an airframe problem...

Eclipse management finally convinced the Board that the problems

were not going to get solved. The Board was sympathetic, but wanted

to be sure. They hired a world-class consultant -- everybody uses

him, and everybody agrees he's tops -- and told Williams he would

look into things. The Board demanded that the consultant have

access to everything at Williams that pertained to our program --

they hadn't let us see much of anything until then." Raburn

continued, noting the good news and the bad.

The good news was that, "Our expert was given

everything;" and the bad news was that he wrote, "a scathing

report, that said Williams was 2, maybe 3 years from certification.

Williams had never done such things. Some of the things they were

trying to do had never been done, by anyone, on any size

engine."

Raburn took a deep breath. "Finally, I got permission from the

Board, and kicked them out. There was a lot of gnashing of teeth...

We had a legal argument; they had a contract. We could get into the

business of suing people, sort of 'Eclipse LLC,' and let the

Eclipse [airplane] meanwhile just kind of go away; or we could

terminate the agreement."

Facing the great

unknown of just what suitable engine would become available,

Eclipse set about testing two sides of the market: it asked its

customers which jet engine producer they would prefer, and they

asked manufacturers what engines would be available, and in what

timeframe.

Facing the great

unknown of just what suitable engine would become available,

Eclipse set about testing two sides of the market: it asked its

customers which jet engine producer they would prefer, and they

asked manufacturers what engines would be available, and in what

timeframe.

"This was a very difficult time, Raburn remembered, "even though

we had our vision, these are BIG companies -- and they had to act

in a way in which they weren't accustomed to acting. Each company

had its 'Eclipse supporters' inside, and each group of supporters

needed to work hard to convince its Board."

Tension built, as the time ticked away...

"We were fighting for our lives," Raburn recalled, "and they

were making $100 million decisions in what was an unquestionably an

unfriendly economy, and an unfriendly environment, overall."

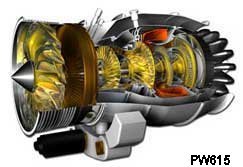

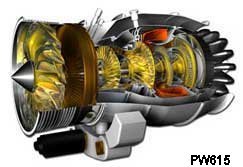

"It's remarkable," Vern said, "that a Fortune 25 company, within

75 days, went from an initial decision to an official Memorandum of

Understanding. Pratt deserves a ton of credit. All those

stereotypes -- that big companies can't make decisions, that big

companies can't move, that big companies don't even listen to

customers -- all those stereotypes got blown out the

window at Pratt."

Everything was different with P&W.

"Pratt has a very

different approach to engineering than Williams," Raburn said.

"Williams just isn't as analytical." For instance? "When Pratt

& Whitney got much better than expected SFC (specific fuel

consumption) on the 625 than they predicted, they ordered a whole

new program, put the engines back on the aircraft, to determine

why. When Williams had that kind of thing happen, they just

adjusted from that point forward."

"Pratt has a very

different approach to engineering than Williams," Raburn said.

"Williams just isn't as analytical." For instance? "When Pratt

& Whitney got much better than expected SFC (specific fuel

consumption) on the 625 than they predicted, they ordered a whole

new program, put the engines back on the aircraft, to determine

why. When Williams had that kind of thing happen, they just

adjusted from that point forward."

The future is now.

"Pratt is putting a lot of their

own money into this," Mr. Raburn noted. "The 600 series [engine] is

the end of the line for the PT-6, for that whole class of transport

turboprops. You'll always have propellers, but for transportation,

the propellers' days, or at least years, are numbered."

"Pratt is putting a lot of their

own money into this," Mr. Raburn noted. "The 600 series [engine] is

the end of the line for the PT-6, for that whole class of transport

turboprops. You'll always have propellers, but for transportation,

the propellers' days, or at least years, are numbered."

Just to be sure:

"An informal survey we took among a hundred of our customers --

we admit, we didn't do it scientifically -- gave us an interesting

result," Raburn added. "We asked them, among the four -- GE,

Rolls-Royce, Honeywell, and Pratt & Whitney -- which they would

prefer to power their airplanes (assuming all manufacturers could

do it), which would they pick. 100% -- really, every one -- picked

Pratt." So did Eclipse.

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.09.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.09.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.09.25): High Speed Taxiway

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.09.25): High Speed Taxiway ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.09.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.09.25) NTSB Final Report: Diamond Aircraft Ind Inc DA20C1 (A1); Robinson Helicopter R44

NTSB Final Report: Diamond Aircraft Ind Inc DA20C1 (A1); Robinson Helicopter R44 ANN FAQ: Q&A 101

ANN FAQ: Q&A 101