Group Demands More Commercial Access To Space

A group of space activists, led by a new sub-orbital industry

organization, stormed Capitol Hill earlier this month, hoping to

talk to legislators about regulatory reforms to help promote the

incipient suborbital reusable launch industry.

About a dozen member of the newly-formed Suborbital Institute

went door-to-door to more than two dozen members of Congress during

the one-day event, wryly dubbed "Love & Rockets" because of the

event's proximity to Valentine's Day and the strong interest the

organization's members have in suborbital spaceflight.

SI To Congress: Ease Up!

The goal of the Suborbital Institute's first Congressional

briefing was to let Congress know about the efforts of a number of

entrepreneurial companies trying to develop reusable vehicles

capable of suborbital spaceflight. The Institute expedition also

hoped to ease the regulatory hurdles that lie in the path of these

firms.

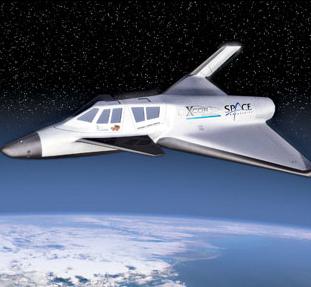

Suborbital spacecraft are vehicles that fly into space,

typically to altitudes of at least 100 kilometers, but do not

travel fast enough to attain orbit. Currently only unmanned

sounding rockets perform suborbital flight, but a number of

companies, primarily small entrepreneurial efforts, are currently

developing reusable, manned spacecraft for suborbital flights.

This new push for manned suborbital spaceflight

comes mainly from two sources. One is the X Prize, a $10 million

competition to develop the first reusable suborbital spacecraft

capable of carrying three people to an altitude of 100 km twice in

a two-week period. The other has been the collapse in demand for

commercial launches, driven by the failure of ventures like Iridium

and Teledesic, forcing companies that were once interested in

developing orbital reusable launch vehicles (RLVs) to explore

suborbital markets.

This new push for manned suborbital spaceflight

comes mainly from two sources. One is the X Prize, a $10 million

competition to develop the first reusable suborbital spacecraft

capable of carrying three people to an altitude of 100 km twice in

a two-week period. The other has been the collapse in demand for

commercial launches, driven by the failure of ventures like Iridium

and Teledesic, forcing companies that were once interested in

developing orbital reusable launch vehicles (RLVs) to explore

suborbital markets.

While suborbital spaceflight has been most closely linked to

space tourism, there are a number of other markets for such

vehicles. A report by the Department of Commerce published last

December identified a number of possible uses for suborbital

spacecraft, from microgravity experimentation to remote sensing.

Suborbital vehicles also provide "an incremental approach that will

lead to commercial orbital RLVs," said Paula Trimble, an analyst

with the Commerce Department's Office of Space Commercialization,

during a breakfast meeting that preceded the day's lobbying

efforts.

How Do You Classify That, Anyway?

Suborbital spaceflight does bring up a number of regulatory

issues, notably with the FAA. Kelvin Coleman, special assistant for

programs and planning with the FAA's Office of the Associate

Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation (AST), said that

suborbital flight falls "right near the line of aviation

operations." This makes it unclear whether such vehicles should be

regulated like launch vehicles or like high-performance aircraft.

"We at FAA are challenged to figure out where that line is,"

Coleman said.

Suborbital spaceflight does bring up a number of regulatory

issues, notably with the FAA. Kelvin Coleman, special assistant for

programs and planning with the FAA's Office of the Associate

Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation (AST), said that

suborbital flight falls "right near the line of aviation

operations." This makes it unclear whether such vehicles should be

regulated like launch vehicles or like high-performance aircraft.

"We at FAA are challenged to figure out where that line is,"

Coleman said.

When XCOR Aerospace, a California company developing a

suborbital RLV, conducted flight tests of its EZ Rocket

rocket-powered airplane, it got an experimental aircraft license

from the FAA because it provided more flexibility than a launch

license, as each flight could theoretically require obtaining a

separate license. AST is aware of those concerns, Coleman said, and

has recently published an advisory circular explaining how the

current rules could be used by XCOR and other companies to fly test

regimes without getting a separate launch license for each

flight.

Nonetheless, one of the key talking points the Suborbital

Institute made for its day on the Hill was to promote a "flexible

model of regulation" that allows for the type of flexibility a

young industry like suborbital spaceflight needs. Pat Bahn, founder

and CEO of TGV Rockets and a founder of the Suborbital Institute,

said that he's "70 percent happy" with what the FAA has done to

date, adding that "their hearts are in the right place and they're

trying very hard."

Who'll Pay If It Falls Down?

Besides FAA regulation, another key point for the Suborbital

Institute is insurance. The current insurance environment isn't

suitable for suborbital RLVs, as launch insurance was designed for

expendable vehicles and commercial aviation insurance is unwilling

to provide enough insurance to cover the maximum probable loss

determined by the FAA. The Institute believes the federal

government should step in to help fill the gap between what is

required and what is currently offered. The Institute also

advocates the creation of multiple spaceports around the country

for use by suborbital RLVs, rather than a single national spaceport

like Cape Canaveral.

Columbia Tragedy: No Effect on Industry

The

Institute, whose corporate members include TGV, XCOR, Armadillo

Aerospace, and X-Rocket LLC, doesn't think that the loss of the

space shuttle Columbia earlier this month will have a major impact

on their efforts. "We have a real opportunity here, better than we

had a week ago, as even in the public's eye it's clear that the way

we are developing space isn't working," said Earl Renaud, chief

operating officer of TGV. "We need to get the message out that

there are people who want to do this and they need the government's

support, or at least step back and not hinder the industry."

The

Institute, whose corporate members include TGV, XCOR, Armadillo

Aerospace, and X-Rocket LLC, doesn't think that the loss of the

space shuttle Columbia earlier this month will have a major impact

on their efforts. "We have a real opportunity here, better than we

had a week ago, as even in the public's eye it's clear that the way

we are developing space isn't working," said Earl Renaud, chief

operating officer of TGV. "We need to get the message out that

there are people who want to do this and they need the government's

support, or at least step back and not hinder the industry."

For Bahn, who started TGV Rockets several years ago as a

suborbital company when most entrepreneurial efforts were focused

on orbital RLVs, the growth in interest in suborbital vehicles has

been something of a vindication. "I've been out in the wilderness

for a while," he said, "and now I've found that it's turned into a

minor suburb."

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.03.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.03.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.03.25): CrewMember (UAS)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.03.25): CrewMember (UAS) NTSB Prelim: Maule M-7-235A

NTSB Prelim: Maule M-7-235A Airborne-Flight Training 12.04.25: Ldg Fee Danger, Av Mental Health, PC-7 MKX

Airborne-Flight Training 12.04.25: Ldg Fee Danger, Av Mental Health, PC-7 MKX Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.04.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.04.25)