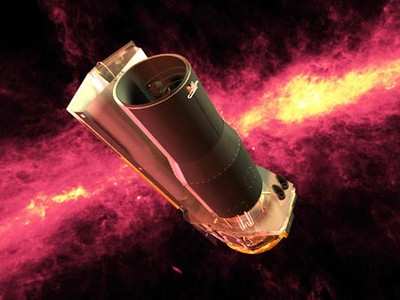

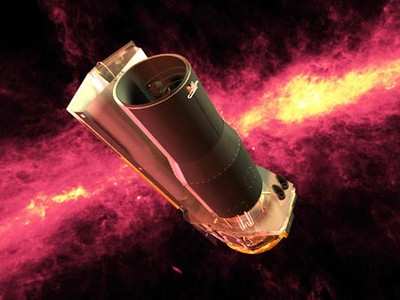

Spitzer Continues To Amaze Researchers

For the first time ever, a NASA telescope has captured enough

light from planets outside Earth's solar system to identify

individual molecules present in their atmospheres. The space agency

says data obtained by the Spitzer Space Telescope is a significant

step toward being able to detect possible life on rocky exoplanets,

and comes years before astronomers had anticipated.

"This is an amazing surprise," said Spitzer project scientist

Dr. Michael Werner of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena,

CA. "We had no idea when we designed Spitzer that it would make

such a dramatic step in characterizing exoplanets."

Spitzer, a space-based infrared telescope, obtained the detailed

data, called spectra, for two different gas exoplanets. Called HD

209458b and HD 189733b, these so-called "hot Jupiters" are, like

Jupiter, made of gas, but orbit much closer to their suns.

The data indicate the two planets are drier and cloudier than

predicted. Theorists thought hot Jupiters would have lots of water

in their atmospheres, but surprisingly none was found around HD

209458b and HD 189733b.

According to astronomers, water might still be present -- but

buried under a thick blanket of high, waterless clouds that may be

filled with dust.

One of the planets, HD 209458b, showed hints of tiny sand

grains, called silicates, in its atmosphere. (Need a visual?

Think Phoenix, AZ during a summertime wind storm -- times 100...

Ed.) NASA theorizes this could mean the planet's skies are

filled with high, dusty clouds unlike anything seen around planets

in our own solar system.

One of the planets, HD 209458b, showed hints of tiny sand

grains, called silicates, in its atmosphere. (Need a visual?

Think Phoenix, AZ during a summertime wind storm -- times 100...

Ed.) NASA theorizes this could mean the planet's skies are

filled with high, dusty clouds unlike anything seen around planets

in our own solar system.

"The theorists' heads were spinning when they saw the data,"

said Dr. Jeremy Richardson of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in

Greenbelt, MD.

"It is virtually impossible for water, in the form of vapor, to

be absent from the planet, so it must be hidden, probably by the

dusty cloud layer we detected in our spectrum," he said.

A spectrum is created when an instrument called a spectrograph

splits light from an object into its different wavelengths, just as

a prism turns sunlight into a rainbow. The resulting pattern of

light, the spectrum, reveals "fingerprints" of chemicals making up

the object.

Until now, the only planets for which spectra were available

belonged in our own solar system. The planets in the Spitzer

studies orbit stars that are so far away, they are too faint to be

seen with the naked eye. HD 189733b is 370 trillion miles away in

the constellation Vulpecula, and HD 209458b is 904 trillion miles

away in the constellation Pegasus. That means both planets are at

least about a million times farther away from us than Jupiter.

In the future, astronomers hope to have spectra for smaller,

rocky planets beyond our solar system. This would allow them to

look for the footprints of life -- molecules key to the existence

of life, such as oxygen and possibly even chlorophyll.

"With these new observations, we are refining the tools that we

will one day need to find life elsewhere if it exists," said Dr.

Mark R. Swain of JPL. "It's sort of like a dress rehearsal."

Previous observations of HD 209458b by NASA's Hubble Space

Telescope revealed individual elements, such as sodium, oxygen,

carbon and hydrogen, that bounce around the very top of the planet,

a region higher up than that probed in the Spitzer studies and a

region where molecules like water would break apart.

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.06.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.06.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.06.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.06.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF) ANN FAQ: Q&A 101

ANN FAQ: Q&A 101 Classic Aero-TV: Virtual Reality Painting--PPG Leverages Technology for Training

Classic Aero-TV: Virtual Reality Painting--PPG Leverages Technology for Training Airborne 05.02.25: Joby Crewed Milestone, Diamond Club, Canadian Pilot Insurance

Airborne 05.02.25: Joby Crewed Milestone, Diamond Club, Canadian Pilot Insurance