Boeing Thermal Engineer: "I've Never Seen A Strike This

Big."

Veteran engineers at shuttle contractor Boeing say

their company falsely led NASA officials to believe the space

shuttle Columbia was safe to land because top managers

assigned the task of assessing launch damage to Boeing workers

who'd never done that type of analysis before.

Veteran engineers at shuttle contractor Boeing say

their company falsely led NASA officials to believe the space

shuttle Columbia was safe to land because top managers

assigned the task of assessing launch damage to Boeing workers

who'd never done that type of analysis before.

The Sunday edition of the Miami Herald quotes a thermal

systems engineer who did this kind of analysis for 10 years in

California before Boeing shifted the work to its Houston offices

last year as saying, "I think they wanted to paint a rosy picture,

and they did. In my experience, I have never seen a strike this

big."

"I think they are trying to build a case to protect their asses

for running with faulty thermal analysis."

Herald interviews with engineers at the Boeing plant in

Huntington Beach (CA), lend credence to claims by experts outside

NASA who say Boeing made huge mistakes in its evaluation of wounds

the shuttle may have suffered when debris slammed into its left

wing during lift-off.

In an internal e-mail at Boeing/Huntington Beach, an unnamed

employee speculated NASA has been downplaying the debris strike to

fend off criticism the space agency might not have done enough to

get the astronauts home safely.

"The NASA boys are `back-pedaling' on the original theory of

debris impact," the Boeing employee wrote. "I think they are trying

to build a case to protect their asses for running with faulty

thermal analysis."

Several engineers here began their own analysis after the crash

- using the same data and procedures that were used in Houston

during the flight. The Herald reports those results are

not only different, but they indicate that NASA had an emergency on

its hands.

"We're redoing the analysis because we think it needs to be done

differently," said another longtime shuttle engineer, an expert at

calculating debris impact. "The re-analysis is finding things to be

more harsh than the original."

An independent panel investigating the disaster has so far

determined only that some type of breach allowed searing gases to

enter the shuttle and melt its aluminum frame.

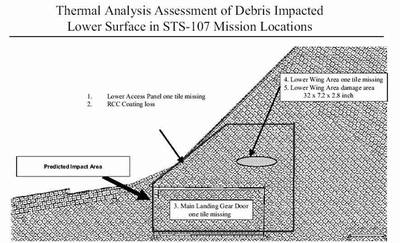

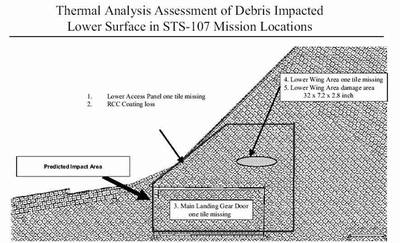

One possible cause of this is that the orbiter's

thermal-protective tiles were damaged or missing, leaving the

ship's thin aluminum skin vulnerable to a "burn-through."

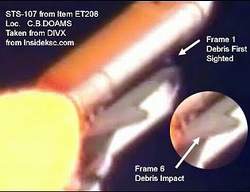

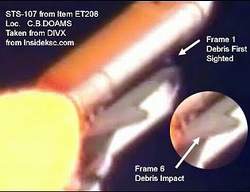

When debris sloughed off the external fuel tank 81 seconds into

launch and hit the wing, engineers began focusing on just such a

contingency. With Columbia still in flight, NASA asked

Boeing to evaluate whether the damage could flare up into a

burn-through during re-entry.

First Flight For Boeing Houston Team

The

engineers at Boeing's plant in Huntington Beach, Calif., say they

had done these analyses for 20 years. But this year, they were not

asked to.

The

engineers at Boeing's plant in Huntington Beach, Calif., say they

had done these analyses for 20 years. But this year, they were not

asked to.

The reason, they say: Boeing transferred shuttle jobs to Houston

in a consolidation that has cost the company scores of its most

experienced shuttle engineers during the past two years - including

some of those who invented the methodology for debris damage and

thermal analysis.

As Columbia headed toward re-entry, Boeing managers

instead relied on a Houston-based team of engineers who had never

done this type of analysis in a real situation.

"This was their first flight," said the Boeing thermal systems

engineer. "This was the first time they took over."

Boeing spokeswoman Kari Allen said Friday she didn't know if

that was true. "There's a whole lot of people who put that analysis

together. Just because there were four names on the front doesn't

mean there weren't many other people."

The Houston team analyzed a number of scenarios, ultimately

predicting a "safe return" for Columbia. Boeing executives

say that analysis as the "best answers possible" from the "best

technical minds." On Friday, Allen said the company "absolutely"

stood by that statement, even as new e-mails released from NASA

last week suggested some inside the agency voiced strong

doubts.

The Miami Herald reports Boeing's Huntington Beach

engineers - who helped invent the process - say the Boeing team in

Houston grossly mis-analyzed the data.

"Basically, they just didn't interpret the numbers right," the

thermal systems engineer said. "They never properly identified the

risk."

Four Boeing employees and contractors spoke for this report.

Each has at least a decade of experience with the shuttle program.

They say company vice presidents ordered them not to talk to the

press in a Feb. 13 meeting in the company cafeteria.

Their interviews with The Miami Herald echo the

statements of numerous outside experts who have said the thermal

analysis were flawed. And they raise a haunting question in the

aftermath of the Feb. 1 shuttle disintegration: Could NASA have

saved the seven astronauts had it properly assessed the risk?

Crater Program Disregarded?

After the disaster, the California engineers say they were

shocked to see the data that Boeing and NASA used to reach their

conclusions. One chart relied on a computer program called "Crater"

to come up with nine different damage scenarios. Any one of them

could have been catastrophic, the thermal engineer here said, but

the Houston analysts downplayed the results by saying that "Crater"

tended to be conservative.

Outside experts say it makes no sense to have

rejected methods that brought other shuttles home safely.

Outside experts say it makes no sense to have

rejected methods that brought other shuttles home safely.

One scenario, for example, predicted a two-foot-long,

seven-inch-wide swath of missing tiles.

"When something like that hits you and your computer program

tells you you're all the way through the thermal protection system

for that big of an area, you're in big trouble," the thermal

systems engineer said.

"We had never seen a chart as bad as that."

The evaluation, completed on January 23, assumed only one

piece of debris hit the shuttle. Yet a January 24 debris impact

analysis showed that three pieces of debris may have struck the

orbiter ("Columbia Hit By Foam As Many As Three Times,"

ANN, Feb. 23, 2003).

Was Anybody Listening?

At this point, there is some question as to whether the

consequences of a possible triple impact were ever addressed.

During past flights, when shuttles sustained even minor tile

damage, the Boeing thermal analysis team warned NASA managers of

potential risks so they could take preventive measures.

When Atlantis flew in May 2000, for example, a smaller debris

strike prompted flight directors to take a safety measure called

"cold soaking" before the ship hit the atmosphere. This means they

positioned the damaged area so it faced away from the sun, leaving

it extra cold by the time it was subjected to the heat of re-entry.

Atlantis landed at night.

NASA managers have also speculated that, if there was a serious

risk of one wing falling apart, the shuttle could come in at a

slightly different angle to put more heat on the good wing.

After the crash, NASA has repeatedly tried to downplay the

possibility that damage caused by the debris that hit the orbiter's

left wing actually led to the crash. Last week, NASA Administrator

Sean O'Keefe mocked reporters for focusing so much on foam, calling

them "foamologists."

But the internal e-mails circulating among Boeing engineers in

Huntington Beach shows at least some have lingering doubts.

"NASA and Boeing Management are doing whatever they can to

redirect attention away from that thermal analysis that was done by

inexperienced thermal engineers rather than the guys that would

normally have done it," it says.

NTSB Final Report: Dehavilland DHC-2 MK 1

NTSB Final Report: Dehavilland DHC-2 MK 1 Aero-News: Quote of the Day (10.29.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (10.29.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.29.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.29.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (10.30.25): Minimum Friction Level

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (10.30.25): Minimum Friction Level ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.30.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.30.25)