Cost-Consciousness Could Have Killed Columbia

When the

Columbia Accident Investigation Board releases its final

report, sometime before Labor Day, it will likely be a blistering

blow to NASA. The board will probably recommend major changes in

the space agency's "culture," as well as creation of an independent

body to oversee flight safety issues. But will the CAIB address the

bottom-line issues that may have contributed more than any other to

the Columbia disaster?

When the

Columbia Accident Investigation Board releases its final

report, sometime before Labor Day, it will likely be a blistering

blow to NASA. The board will probably recommend major changes in

the space agency's "culture," as well as creation of an independent

body to oversee flight safety issues. But will the CAIB address the

bottom-line issues that may have contributed more than any other to

the Columbia disaster?

We're Talking Money Here

Now, to be fair, NASA doesn't appropriate its own budget. The

space agency makes a request, it becomes part of the president's

budget and it gets mauled on Capitol Hill. Whatever Washington

sends, NASA pretty much has to live with. Budgetary constraints

were seen as a factor in the 1986 Columbia disaster. Now,

it looks like those same sort of constraints helped doom

Columbia.

The most experienced shuttle engineers in the world work at the

Boeing plant in Huntington Beach (CA). They have more than 18

years' experience in thermal applications with specific regard to

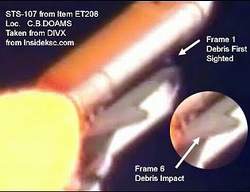

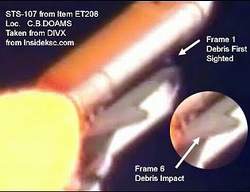

the shuttle program. But when, shortly after Columbia's

last launch on January 16th, a chunk of insulating foam broke free

of the external fuel tank and slammed into the shuttle's left wing,

NASA didn't call on the Huntington Beach team.

Why?

As ANN reported earlier this year (ANN: February 24, 2003 -

"Is Columbia Plagued By

Inexperience?"), Boeing transferred shuttle jobs to

Houston in a consolidation that has cost the company scores of its

most experienced shuttle engineers over the past two years --

including some of those who invented the methodology for debris

damage and thermal analysis.

While Columbia was still early in its mission, Boeing

managers relied on the Houston-based team of engineers who had

never done this type of analysis in a real situation.

"This was their first flight," said an anonymous Boeing thermal

systems engineer. "This was the first time they took over."

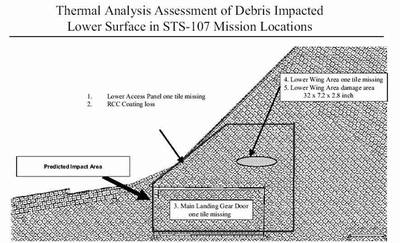

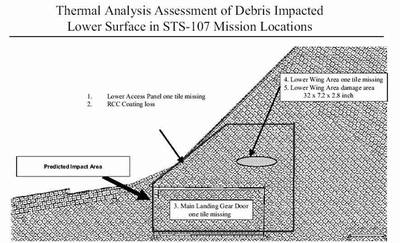

The Houston team analyzed a number of scenarios, ultimately

predicting a "safe return" for Columbia. Boeing executives say that

analysis as the "best answers possible" from the "best technical

minds." On Friday, Allen said the company "absolutely" stood by

that statement, even as new e-mails released from NASA last week

suggested some inside the agency voiced strong doubts.

The Miami Herald reported Boeing's Huntington Beach

engineers -- who helped invent the process -- say the Boeing team

in Houston grossly mis-analyzed the data.

"Basically, they just didn't interpret the numbers right," the

thermal systems engineer said. "They never properly identified the

risk."

Their interviews with The Miami Herald echo the

statements of numerous outside experts who have said the thermal

analysis were flawed. And they raise a haunting question in the

aftermath of the February 1 shuttle disintegration: Could NASA have

saved the seven astronauts had it properly assessed the risk?

After the disaster, the California engineers say they were

shocked to see the data that Boeing and NASA used to reach their

conclusions. One chart relied on a computer program called "Crater"

to come up with nine different damage scenarios. Any one of them

could have been catastrophic, the thermal engineer here said, but

the Houston analysts downplayed the results by saying that "Crater"

tended to be conservative.

"When something like that hits you and your computer program

tells you you're all the way through the thermal protection system

for that big of an area, you're in big trouble," the thermal

systems engineer said. "We had never seen a chart as bad as

that."

NASA managers have also speculated that, if there was a serious

risk of one wing falling apart, the shuttle could come in at a

slightly different angle to put more heat on the good wing.

After the crash, NASA has repeatedly tried to downplay the

possibility that damage caused by the debris that hit the orbiter's

left wing actually led to the crash. Last week, NASA Administrator

Sean O'Keefe mocked reporters for focusing so much on foam, calling

them "foamologists."

But the internal e-mails circulating among Boeing engineers in

Huntington Beach show at least some have lingering doubts.

"NASA and Boeing Management are doing whatever they can to

redirect attention away from that thermal analysis that was done by

inexperienced thermal engineers rather than the guys that would

normally have done it," it says.

Fatal Cost-Cutting?

There are two dynamics

at play here. In the first, Congress (and therefore NASA) tightens

the budget. After all, there are many on Capitol Hill who'd just as

soon see the manned space program scrapped. They view it as a waste

of resources. NASA, therefore, cuts funding to contractors as a

result of the axe-weilding in Washington.

There are two dynamics

at play here. In the first, Congress (and therefore NASA) tightens

the budget. After all, there are many on Capitol Hill who'd just as

soon see the manned space program scrapped. They view it as a waste

of resources. NASA, therefore, cuts funding to contractors as a

result of the axe-weilding in Washington.

The second part of the equation is the NASA-think of doing

things "better, faster cheaper," as a result of the cutbacks.

Instead of re-evaluating its programs and priorities in the face of

cutbacks, NASA managers instead did all they could to cram their

original agenda into a budget three sizes too small.

Perhaps there was a sense of complacency about foam strikes on

lifting orbiters. Still, because of budgetary concerns, the best

minds capable of analyzing damage to the thermal tiles on the left

wing's leading edge were left out of the loop.

Aero-News has long supported NASA and the amazing people who

work for the space agency. That won't change. Yet, in the face of

budget constraints, the term "getting the biggest bang for the

buck" has taken on a new meaning of tragic proportions. As the CAIB

finalizes its report to America, we hope it will address the "do

more with less" attitude. Perhaps it's time for NASA to do less

with less -- and make what is done as near-perfect as possible.

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.09.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.09.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.09.25): High Speed Taxiway

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.09.25): High Speed Taxiway ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.09.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.09.25) NTSB Final Report: Diamond Aircraft Ind Inc DA20C1 (A1); Robinson Helicopter R44

NTSB Final Report: Diamond Aircraft Ind Inc DA20C1 (A1); Robinson Helicopter R44 ANN FAQ: Q&A 101

ANN FAQ: Q&A 101