Retired Airline Capt. Tries To Duplicate 1903 Flight

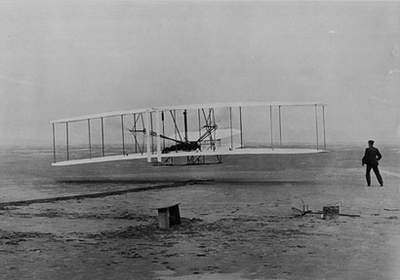

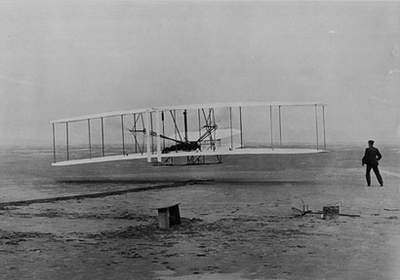

For a few moments inside a frigid NASA wind tunnel, Ken Hyde's

quest to replicate the world's first powered airplane felt

complete.

Hand-carved propellers, spinning for the first time on his replica

1903 Wright flyer, whirred like giant pinwheels. Chains turning

shafts clattered in ways unheard for 100 years. The small crowd

watching erupted in applause.

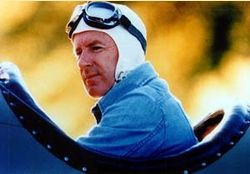

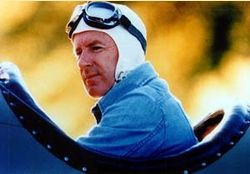

Retired airline pilot Ken Hyde of Warrenton (VA), is building

the flyer that will attempt to duplicate the Wright brothers' first

flight at centennial celebrations in December in Kill Devil

Hills.

Short-Lived Applause

But the work was not done. When the motor stopped, Hyde

dispatched a craftsman to check the rear edge of the top wing. As

Bill Hadden pressed, a metallic pop silenced the clapping. Two

wooden wing ribs had fractured.

"When you've got an airplane that belongs in a museum in an air

tunnel, you're going to have problems," said Kevin Kochersberger, a

mechanical engineering professor at the Rochester Institute of

Technology who is studying Hyde's plane.

Hyde is building the plane that, in December, will attempt to

duplicate the famed Wright brothers' first flight on that very same

spot near the North Carolina coast. This month he towed the nearly

finished aircraft to Langley Air Force Base for tests that could

clarify exactly what the Wrights accomplished in 1903.

It's Never Easy

Nuisances stalked Hyde's team during the first week at Langley

Full Scale Tunnel, a giant, NASA-owned facility built during the

Great Depression to permit engineers to test full-size aircraft

without them leaving the ground.

No accurate blueprints of the Wright flyer exist.

So Hyde's team, a mix of paid staff, independent researchers and

volunteers, has hunted down surviving plane parts, Wright logs,

writings and photographs for guidance. As problems emerged in

Hampton, they consulted with wind tunnel staff and volunteers -

some veterans of NASA moon and Mars missions - made fixes and moved

on.

No accurate blueprints of the Wright flyer exist.

So Hyde's team, a mix of paid staff, independent researchers and

volunteers, has hunted down surviving plane parts, Wright logs,

writings and photographs for guidance. As problems emerged in

Hampton, they consulted with wind tunnel staff and volunteers -

some veterans of NASA moon and Mars missions - made fixes and moved

on.

Hyde had the entire bottom wing of the plane sheathed in clingy

plastic wrap one night to protect it from raccoons. Just in case,

he left a radio blasting classic rock overnight and set a baited

trap, too. Hyde summoned a fabric conservator to work on the fabric

stains. She had luck with the paw prints.

Harry Combs, formerly a president of Learjet, has commissioned a

second for the National Park Service to display at Kill Devil

Hills. Hyde, who doesn't disclose the cost of his planes, is

looking for a sponsor for the third.

1903 Design. 2003 Testing Methodology

On Feb. 14, after seven long workdays at Langley,

the first flyer was ready for the hoist onto the tunnel's test

station. Technicians had reconfigured a steel test stand to make

sure the mostly wood and cloth aircraft would hold tight when the

tunnel's two 35-foot-high fans started blowing air.

On Feb. 14, after seven long workdays at Langley,

the first flyer was ready for the hoist onto the tunnel's test

station. Technicians had reconfigured a steel test stand to make

sure the mostly wood and cloth aircraft would hold tight when the

tunnel's two 35-foot-high fans started blowing air.

A ceiling lift on pulleys raised the aircraft about 15 feet and

stopped while all the helpers scrambled up onto the testing floor.

As he ran up stairs, Rawlings noted how much the plane looked then

like the famous rebuilt flyer in the entryway of the National Air

and Space Museum in Washington.

"Only this," he said, "is accurate."

Once attached to the test stand, bathed in the film crew's

carefully placed lights, the flyer looked more like a piece of art

than a machine. Silver bracing wires glistened. Pale muslin

glowed.

Ultimately the tests could settle lingering disputes over

whether the famous Wright flyer was merely a kite with an engine

that was assisted in lifting by winds exceeding 20 mph or a true

airplane capable of taking off on a windless day.

"The underlying feeling is that we're doing something right for

history," said Drew Landman, an engineering professor at Old

Dominion University also studying the aircraft. "The Wrights did a

lot of things, but they could not do this."

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.30.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.30.25) ANN FAQ: Turn On Post Notifications

ANN FAQ: Turn On Post Notifications Classic Aero-TV: Agile Aeros Jeff Greason--Disruptive Aerospace Innovations

Classic Aero-TV: Agile Aeros Jeff Greason--Disruptive Aerospace Innovations Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.30.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.30.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.30.25): Expedite

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.30.25): Expedite