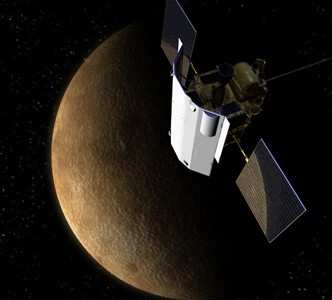

MESSENGER Will Make Three Flights Past Planet

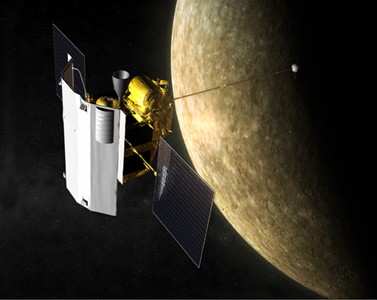

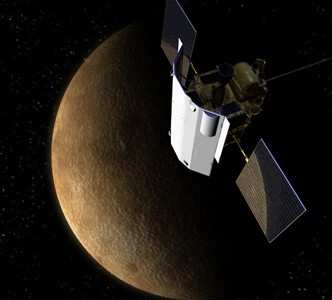

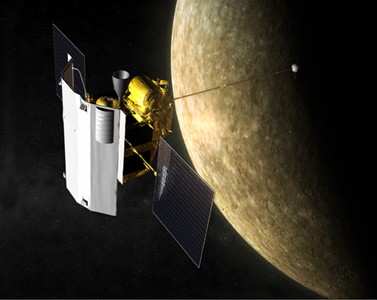

On Monday, a pioneering NASA spacecraft will be the first to

visit Mercury in almost 33 years when it soars over the planet to

explore and snap close-up images of never-before-seen terrain.

These findings could open new theories and answer old questions in

the study of the solar system.

The MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and

Ranging spacecraft -- called MESSENGER -- is the first mission sent

to orbit the planet closest to our sun. Before that orbit begins in

2011, the probe will make three flights past the small planet,

skimming as close as 124 miles above Mercury's cratered, rocky

surface. MESSENGER's cameras and other sophisticated,

high-technology instruments will collect more than 1,200 images and

make other observations during this approach, encounter and

departure.

MESSENGER will make the first up-close measurements since

Mariner 10 spacecraft's third and final flyby on March 16, 1975.

When Mariner 10 flew by Mercury in the mid-1970s, it surveyed only

one hemisphere.

"This is raw scientific exploration and the suspense is building

by the day," said Alan Stern, associate administrator for NASA's

Science Mission Directorate, Washington. "What will MESSENGER see?

Monday will tell the tale."

This encounter will provide a critical gravity assist needed to

keep the spacecraft on track for its March 2011 orbit insertion,

beginning an unprecedented yearlong study of Mercury. The flyby

also will gather essential data for mission planning.

"During this flyby we will begin to image the hemisphere that

has never been seen by a spacecraft and Mercury at resolutions

better than those acquired by Mariner 10," said Sean C. Solomon,

MESSENGER principal investigator, Carnegie Institution of

Washington. "Images will be in a number of different color filters

so that we can start to get an idea of the composition of the

surface."

One site of great interest is the Caloris basin, an impact

crater about 800 miles in diameter, which is one of the largest

impact basins in the solar system.

"Caloris is huge, about a quarter of the diameter of Mercury,

with rings of mountains within it that are up to two miles high,"

said Louise Prockter, the instrument scientist for the Mercury Dual

Imaging System at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics

Laboratory in Laurel. "Mariner 10 saw a little less than half of

the basin. During this first flyby, we will image the other

side."

MESSENGER's instruments will provide

the first spacecraft measurements of the mineralogical and chemical

composition of Mercury's surface. It also will study the global

magnetic field and improve our knowledge of the gravity field from

the Mariner 10 flyby. The long-wavelength components of the gravity

field provide key information about the planet's internal

structure, particularly the size of Mercury's core.

MESSENGER's instruments will provide

the first spacecraft measurements of the mineralogical and chemical

composition of Mercury's surface. It also will study the global

magnetic field and improve our knowledge of the gravity field from

the Mariner 10 flyby. The long-wavelength components of the gravity

field provide key information about the planet's internal

structure, particularly the size of Mercury's core.

The flyby will provide an opportunity to examine Mercury's

environment in unique ways, not possible once the spacecraft begins

orbiting the planet. The flyby also will map Mercury's tenuous

atmosphere with ultraviolet observations and document the energetic

particle and plasma of Mercury's magnetosphere. In addition, the

flyby trajectory will enable unique particle and plasma

measurements of the magnetic tail that sweeps behind Mercury.

Launched August 3, 2004, MESSENGER is slightly more than halfway

through its 4.9-billion mile journey. It already has flown past

Earth once and Venus twice. The spacecraft will use the pull of

Mercury's gravity during this month's pass and others in October

2008 and September 2009 to guide it progressively closer to the

planet's orbit. Insertion will be accomplished with a fourth

Mercury encounter in 2011.

The MESSENGER project is the seventh in NASA's Discovery Program

of low-cost, scientifically focused space missions. The Applied

Physics Laboratory designed, built and operates the spacecraft and

manages the mission for NASA.

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (07.15.25): Charted Visual Flight Procedure Approach

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (07.15.25): Charted Visual Flight Procedure Approach Aero-News: Quote of the Day (07.15.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (07.15.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (07.15.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (07.15.25) NTSB Final Report: Kjelsrud Gary Kitfox

NTSB Final Report: Kjelsrud Gary Kitfox NTSB Prelim: Cessna A150L

NTSB Prelim: Cessna A150L