Technology Developed For Ariane Rocket Being Adapted To Help Cars Burn Hydrogen

An Austrian manufacturer has adapted technology developed for the Ariane rocket to build clean-burning cars that can use hydrogen instead of gasoline for fuel.

To tap hydrogen's tremendous potential as a fuel, spacecraft must be able to store liquid hydrogen at extremely low temperatures, then feed it smoothly to rocket engines. When ESA was developing its hydrogen-fuelled Ariane rockets, it turned to Austria’s MagnaSteyr to build tightly sealed fuel lines and double-walled storage tanks capable of trapping and holding liquid hydrogen and oxygen. “It’s a technical challenge to handle that correctly,” says Gerald Poellmann, the head of Magnasteyr’s Hydrogen Center of Competence. “The tolerance areas are very small, the sealing needs to be tight, the materials can’t have any cracks, you need to prevent evaporation through the materials.”

“The expertise developed working with ESA on hydrogen storage gave MagnaSteyr a wealth of experience,” says Andrea Kurz from Brimatec, ESA’s Technology Transfer Programme partner in Austria. “It made it possible for the company to enter a new business area. To apply the same technology to a very different high-performance engine, designed for the autobahn rather than outer space.”

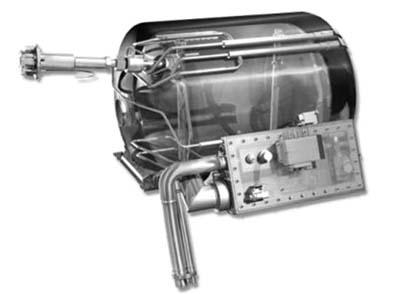

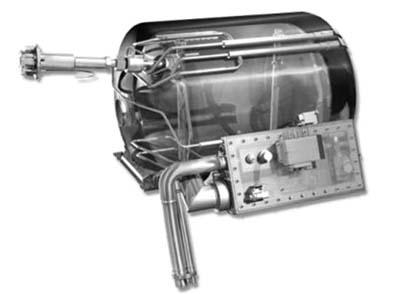

MagnaSteyr worked with German carmaker BMW to develop hydrogen storage tanks small enough to fit in the trunk of a BMW 7 Series sedan. The pilot project succeeded in creating a production car in 2007 that burned hydrogen as fuel, dubbed the BMW Hydrogen 7.

Years of working on Ariane rockets gave MagnaSteyr critical knowhow, Dr Poellmann says: “We used the experience of designing components for hydrogen to apply the technology in this BMW tank.” It was a significant technical achievement. For decades, manufacturers have been trying to figure out how to use hydrogen to power cars.

The challenge for carmakers is working out how to make use of it. To store as a liquid, hydrogen must be kept at –253ºC, which usually requires constant refrigeration. BMW Hydrogen 7 cars store 114 liters (30 gallons) of liquid hydrogen in highly-insulated fuel tanks instead. The equivalent of 55 feet of Styrofoam, the tanks’ insulation can keep the hydrogen cold for almost two weeks. BMW eventually built 100 of the hydrogen-fuelled cars, which also use regular gas. The luxury sedans are still used to shuttle VIPs at special events.

“We learned a lot with those cars,” says BMW spokesman Ralph Huber. “Several million kilometres were driven with them.”

Even if the project proved the worth of liquid hydrogen as an almost pollution-free car fuel, it also highlighted some limitations for which technical solutions need to be found before liquid hydrogen driven cars are to be seen everyday on our roads. One is that as the liquid hydrogen warmed, it boiled into a gas, and was slowly vented off. That meant a driver leaving the car at the airport for two weeks would return to an empty fuel tank. And liquid hydrogen can’t be found at just any filling station: there are fewer than ten pumps in the world equipped to fuel the cars.

Car companies are also looking at fuel cells, which generate electricity from hydrogen and are easier to work with than liquid hydrogen, though not as powerful. Even so, liquid hydrogen needs storage and the MagnaSteyr ‘space-technology’ tanks is a first step along the way.

Whatever form it takes, BMW’s Ralph Huber is sure that “In the long term, hydrogen will be one of our solutions for sustainable mobility.”

The main mission of ESA's Technology Transfer Program is to facilitate the use of space technology and systems for non-space applications, and thereby also further demonstrating realising the benefit of the European space programs to the citizens.

(BMW hydrogen fuel tank image provided by MagnaSteyr)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.03.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (12.03.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.03.25): CrewMember (UAS)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.03.25): CrewMember (UAS) NTSB Prelim: Maule M-7-235A

NTSB Prelim: Maule M-7-235A Airborne-Flight Training 12.04.25: Ldg Fee Danger, Av Mental Health, PC-7 MKX

Airborne-Flight Training 12.04.25: Ldg Fee Danger, Av Mental Health, PC-7 MKX Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.04.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.04.25)