European Venture On Way to Red Planet

The European Mars Express space probe has been

placed successfully in a trajectory that will take it beyond the

terrestrial environment and on the way to Mars; it will arrive in

late December.

The European Mars Express space probe has been

placed successfully in a trajectory that will take it beyond the

terrestrial environment and on the way to Mars; it will arrive in

late December.

This first European Space Agency probe to head for another

planet will enter an orbit around Mars, whence it will perform

detailed studies of the planet’s surface, its subsurface

structures and its atmosphere. It will also deploy Beagle 2, a

small autonomous station which will land on the planet, studying

its surface and looking for possible signs of life, past or

present.

The probe, weighing in at 1,120 kg (about 2500 pounds), was

built on ESA’s behalf by a European team led by Astrium. It

set out on its journey to Mars aboard a Soyuz-Fregat launcher,

under Starsem operational management. The launcher lifted off from

Baïkonur, in Kazakhstan, Monday night, a quarter before

midnight, local time (17:45 Zulu). An interim orbit around the

Earth was reached following a first firing of the Fregat upper

stage. One hour and thirty-two minutes later, the probe was

injected into its interplanetary orbit.

Contact with Mars Express was established by ESOC

"Europe is on its way to Mars to stake its claim

in the most detailed and complete exploration ever done of the Red

Planet. We can be very proud of this and of the speed with which

have achieved this goal," said David Southwood, ESA's Director of

Science, after witnessing the launch from Baikonur. Contact with

Mars Express has been established by ESOC, ESA’s satellite

control center, located in Darmstadt, Germany.

"Europe is on its way to Mars to stake its claim

in the most detailed and complete exploration ever done of the Red

Planet. We can be very proud of this and of the speed with which

have achieved this goal," said David Southwood, ESA's Director of

Science, after witnessing the launch from Baikonur. Contact with

Mars Express has been established by ESOC, ESA’s satellite

control center, located in Darmstadt, Germany.

The probe is pointing correctly towards the Sun and has deployed

its solar panels. All on-board systems are, the agency says,

"operating faultlessly." On Wednesday, the probe will perform a

corrective maneuver that will place it in a Mars-bound trajectory,

while the Fregat stage, trailing behind, will vanish into space

– there will be no risk of its crashing into (contaminating)

the Red Planet.

Mars Express will then travel away from Earth at a speed

exceeding 30 km/s (3 km/s in relation to the Earth), on a six-month

and 400-million kilometer journey through the solar system. Once

all payload operations have been checked out, the probe will be

largely deactivated. During this period, the spacecraft will

contact Earth only once a day. Mid-journey correction of its

trajectory is scheduled for September.

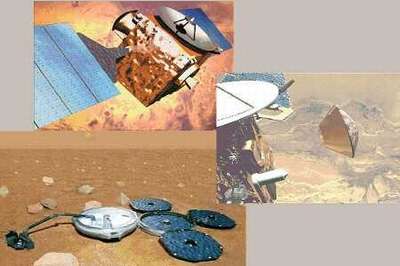

Beagle 2 lander leaving the Mars Express orbiter

Following reactivation of its systems at the end of November,

Mars Express will get ready to release Beagle 2. The 60 kg

capsule containing the tiny lander does not incorporate its own

propulsion and steering system and will be released into a

collision trajectory with Mars, five days before Christmas. It will

enter the Martian atmosphere on Christmas day.

As it descends, the lander will be protected in the first

instance by a heat shield; two parachutes will then open to provide

further deceleration. With its weight down to 30 kg at most, it

will land in an equatorial region known as Isidis Planitia. Three

airbags will soften the final impact. This crucial phase in the

mission will last just ten minutes, from entry into the atmosphere

to landing.

Meanwhile, the Mars Express probe itself will have performed a

series of maneuvers through to a capture orbit. At this point its

main motor will fire, providing the deceleration needed to acquire

a highly-elliptical transition orbit. Attaining the final

operational orbit will call for four more firings. This 7.5 hour

quasi-polar orbit will take the probe to within 250 km of the

planet.

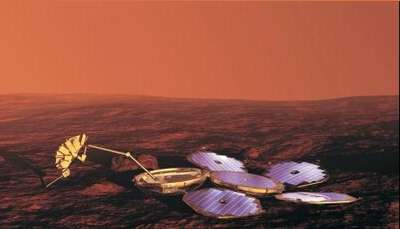

Having landed on Mars, Beagle 2 (named after HMS

Beagle, on which Charles Darwin voyaged round the world) will

deploy its solar panels and the payload adjustable workbench

("PAW"), a set of instruments (two cameras, a microscope and two

spectrometers) mounted on the end of a robot arm.

It will proceed to explore its new environment, gathering

geological and mineralogical data that should, for the first time,

allow rock samples to be dated with reasonable accuracy. Using a

grinder and corer, and the "mole" (a wire-guided mini-robot able to

borrow its way under rocks and dig the ground to a depth of six and

a half feet), samples will be collected and then examined in the

GAP automated mini-laboratory, equipped with 12 furnaces and a mass

spectrometer. The spectrometer will have the job of detecting

possible signs of life and dating rock samples.

The Mars Express orbiter will carry out a detailed investigation

of the planet, pointing its instruments at Mars for between

half-an-hour and an hour per orbit and then, for the remainder of

the time, at Earth to relay the information collected in this way

and the data transmitted by Beagle 2.

The orbiter’s seven on-board instruments are expected to

provide considerable information about the structure and evolution

of Mars. A very high resolution stereo camera, the HRSC, will

perform comprehensive mapping of the planet at 10 meters resolution

and will even be capable of photographing some areas to a precision

of barely 2 meters. The OMEGA spectrometer will draw up the first

mineralogical map of the planet to 100-meter precision.

The orbiter mission should last at least one Martian year (687

days), while Beagle 2 is expected to operate on the

planet’s surface for 180 days. This first European mission to

Mars incorporates some of the objectives of the Euro-Russian Mars

96 mission, which came to grief when the Proton launcher failed.

And indeed a Russian partner is cooperating on each of the

orbiter’s instruments.

Mars

Express forms part of an international Mars exploration program,

featuring also the US probes Mars Surveyor and Mars Odyssey, the

two Mars Exploration Rovers and the Japanese probe Nozomi. Mars

Express may perhaps, within this partnership, relay data from the

NASA rovers while Mars Odyssey may, if required, relay data from

Beagle 2.

Mars

Express forms part of an international Mars exploration program,

featuring also the US probes Mars Surveyor and Mars Odyssey, the

two Mars Exploration Rovers and the Japanese probe Nozomi. Mars

Express may perhaps, within this partnership, relay data from the

NASA rovers while Mars Odyssey may, if required, relay data from

Beagle 2.

The mission’s scientific goals are of outstanding

importance. Mars Express will, it is hoped, supply answers to the

many questions raised by earlier missions – questions

concerning the planet’s evolution, the history of its

internal activity, the presence of water below its surface, the

possibility that Mars may at one time have been covered by oceans

and thus have offered an environment conducive to the emergence of

some form of life, and even the possibility that life may still be

present, somewhere in putative subterranean aquifers. In addition,

the lander's doing direct analysis of the soil and the environment

comprises a truly unique mission.

Next: Venus, 2005.

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.19.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (12.19.25): Ultrahigh Frequency (UHF) NTSB Prelim: Cirrus Design Corp SR22T

NTSB Prelim: Cirrus Design Corp SR22T Classic Aero-TV: The Red Tail Project--Carrying the Torch of the Tuskegee Airmen

Classic Aero-TV: The Red Tail Project--Carrying the Torch of the Tuskegee Airmen Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.19.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (12.19.25) Airborne 12.17.25: Skydiver Hooks Tail, Cooper Rotax Mount, NTSB v NDAA

Airborne 12.17.25: Skydiver Hooks Tail, Cooper Rotax Mount, NTSB v NDAA