But Spirit May Be In Trouble

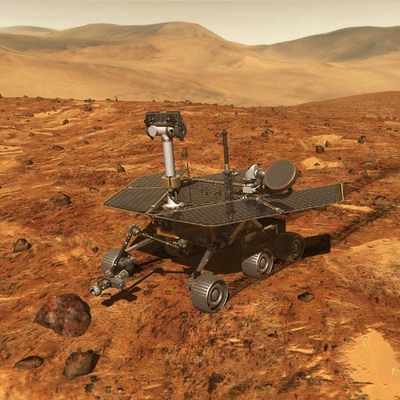

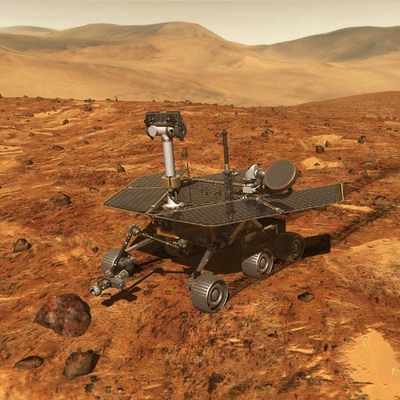

NASA's Spirit and Opportunity have

been exploring Mars about three times as long as originally

scheduled. The more they look, the more evidence of past liquid

water on Mars these robots discover. Team members reported the new

findings at a news briefing today.

NASA's Spirit and Opportunity have

been exploring Mars about three times as long as originally

scheduled. The more they look, the more evidence of past liquid

water on Mars these robots discover. Team members reported the new

findings at a news briefing today.

About six months ago, Opportunity established that its

exploration area was wet a long time ago. The area was wet before

it dried and eroded into a wide plain. The team's new findings

suggest some rocks there may have gotten wet a second time, after

an impact excavated a stadium-sized crater.

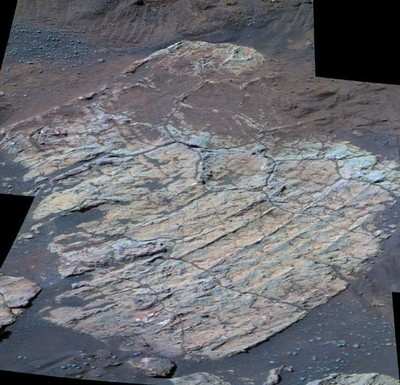

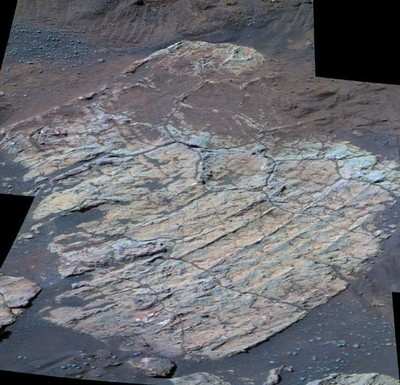

Evidence of this exciting possibility has been identified in a

flat rock dubbed "Escher" and in some neighboring rocks near the

bottom of the crater. These plate-like rocks bear networks of

cracks dividing the surface into patterns of polygons, somewhat

similar in appearance to cracked mud after the water has dried up

here on Earth.

Alternative histories, such as fracturing by the force of the

crater-causing impact, or the final desiccation of the original wet

environment that formed the rocks, might also explain the polygonal

cracks. Rover scientists hope a lumpy boulder nicknamed "Wopmay,"

Opportunity's next target for inspection, may help narrow the list

of possible explanations.

"When we saw these polygonal crack patterns, right away we

thought of a secondary water event significantly later than the

episode that created the rocks," said Dr. John Grotzinger. He is a

rover-team geologist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

in Cambridge (MA). Finding geological evidence about watery periods

in Mars' past is the rover project's main goal, because such

persistently wet environments may have been hospitable to life.

"Did these cracks form after the crater was created? We don't

really know yet," Grotzinger said.

If they did, one possible source of moisture could be

accumulations of frost partially melting during climate changes, as

Mars wobbled on its axis of rotation, in cycles of tens of

thousands of years. According to Grotzinger, another possibility

could be the melting of underground ice or release of underground

water in large enough quantity to pool a little lake within the

crater.

One type of evidence Wopmay could add to the case for wet

conditions after the crater formed would be a crust of

water-soluble minerals. After examining that rock, the rover team's

plans for Opportunity are to get a close look at a tall stack of

layers nicknamed "Burns Cliff" from the base of the cliff. The

rover will then climb out of the crater and head south to the

spacecraft's original heat shield and nearby rugged terrain, where

deeper rock layers may be exposed.

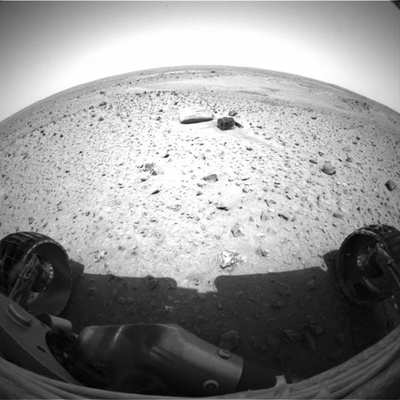

Halfway around Mars, Spirit is climbing higher into the

"Columbia Hills." Spirit drove more than three kilometers

(approximately two miles) across a plain to reach them. After

finding bedrock that had been extensively altered by water,

scientists used the rover to look for relatively unchanged rock as

a comparison for understanding the area's full range of

environmental changes. Instead, even the freshest-looking rocks

examined by Spirit in the Columbia Hills have shown signs of

pervasive water alteration.

"We haven't seen a single unaltered volcanic rock, since we

crossed the boundary from the plains into the hills, and I'm

beginning to suspect we never will," said Dr. Steve Squyres of

Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., principal investigator for the

science payload on both rovers. "All the rocks in the hills have

been altered significantly by water. We're having a wonderful time

trying to work out exactly what happened here."

More clues to deciphering the environmental history of the hills

could lie in layered rock outcrops farther upslope, Spirit's next

targets. "Just as we worked our way deeper into the Endurance

crater with Opportunity, we'll work our way higher and higher into

the hills with Spirit, looking at layered rocks and constructing a

plausible geologic history," Squyres said.

Jim Erickson, rover project manager at JPL, said, "Both Spirit

and Opportunity have only minor problems, and there is really no

way of knowing how much longer they will keep operating. However we

are optimistic about their conditions, and we have just been given

a new lease on life for them, a six-month extended mission that

began Oct. 1. The solar power situation is better than expected,

but these machines are already well past their design life. While

they're healthy, we'll keep them working as hard as possible."

Spirit: Waylaid?

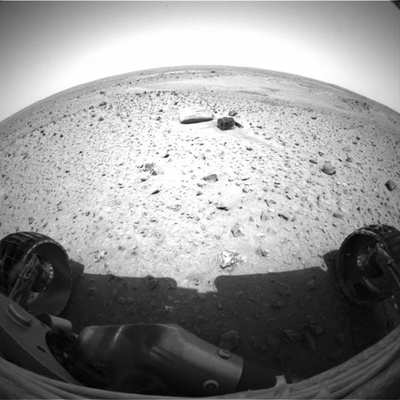

Engineers on NASA's Mars Exploration Rover team are

investigating possible causes and remedies for a problem affecting

the steering on Spirit.

The relay for steering actuators on Spirit's right-front and

left-rear wheels did not operate as commanded on Oct. 1. Each of

the front and rear wheels on the rover has a steering actuator, or

motor, that adjusts the direction in which the wheels are headed

independently from the motor that makes the wheels roll. When the

actuators are not in use, electric relays are closed and the motor

acts as a brake to prevent unintended changes in direction.

Engineers received results Sunday from a first set of diagnostic

tests on the relay. "We are interpreting the data and planning

additional tests," said Rick Welch, rover mission manager at JPL.

"We hope to determine the best work-around if the problem does

persist."

Spirit Opportunity successfully completed their three-month

primary missions in April and five-month mission extensions in

September. They began second extensions of their missions on Oct.

1. Spirit has driven more than 3.6 kilometers (2.2 miles), six

times the distance set as a goal for mission success. It is

climbing into uplands called the "Columbia Hills."

JPL's Jim Erickson, rover project manager, said, "If we do not

identify other remedies, the brakes could be released by a command

to blow the fuse controlling the relay, though that would make

those two brakes unavailable for the rest of the mission." Without

the steering-actuator brakes, small bumps or dips that a wheel hits

during a drive might twist the wheel away from the intended drive

direction.

"If we do need to disable the brakes, errors in drive direction

could increase. However, the errors might be minimized by

continuing to use the brakes on the left-front and right-rear

wheels, by driving in smaller segments, and by adding a software

patch to reset the direction periodically during a drive," Erickson

said. Engineers believe the steering-brake issue is not related to

excessive friction detected during the summer in the drive motor

for Spirit's right-front wheel, because the steering actuator is a

different motor.

Meanwhile, the team continues to use Spirit's robotic arm and

camera mast to study rocks and soils around the rover, without

moving the vehicle until the cause of the anomaly is understood and

corrective measures can be implemented.

Senator Pushes FAA to Accelerate Rocket Launch Licensing

Senator Pushes FAA to Accelerate Rocket Launch Licensing Classic Aero-TV: RJ Gritter - Part of Aviations Bright New Future

Classic Aero-TV: RJ Gritter - Part of Aviations Bright New Future Aero-FAQ: Dave Juwel's Aviation Marketing Stories -- ITBOA BNITBOB

Aero-FAQ: Dave Juwel's Aviation Marketing Stories -- ITBOA BNITBOB ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.27.24)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (10.27.24) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (10.27.24): Clearance Void If Not Off By (Time)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (10.27.24): Clearance Void If Not Off By (Time)