Findings Published Tuesday At American Geophysical Union Meeting

After a year of observations, scientists waited with bated breath on Nov. 28, 2013, as Comet ISON made its closest approach to the sun, known as perihelion. Would the comet disintegrate in the fierce heat and gravity of the sun? Or survive intact to appear as a bright comet in the pre-dawn sky?

Some remnant of ISON did indeed make it around the sun, but it quickly dimmed and fizzled as seen with NASA's solar observatories. This does not mean scientists were disappointed, however. A worldwide collaboration ensured that observatories around the globe and in space, as well as keen amateur astronomers, gathered one of the largest sets of comet observations of all time, which will provide fodder for study for years to come.

On Dec. 10, 2013, researchers presented science results from the comet's last days at the 2013 Fall American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, CA. They described how this unique comet lost mass in advance of reaching perihelion and most likely broke up during its closest approach, as well, as summarized what this means for determining what the comet was made of. "The comet's story begins with the very formation of the solar system," said Karl Battams, an astrophysicist at the Naval Research Lab in Washington, D.C. "The dirty snowball that we came to call Comet ISON was created at the same time as the planets."

ISON circled the solar system in the Oort cloud, more than 4.5 trillion miles away from the sun. At some point a few million years ago, something occurred – perhaps the passage of a nearby star – to knock ISON out of its orbit and send it hurtling along a path for its first trip into the inner solar system.

The comet was first spotted 585 million miles away in September 2012 by two Russian astronomers: Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok. The comet was named after the project that discovered it, the International Scientific Optical Network, or ISON, and given an official designation of C/2012 S1 (ISON). When comet scientists mapped out Comet ISON's orbit they learned that the comet would swing within 1.1 million miles of the sun's surface, making it what's known as a sungrazing comet, providing opportunities to study this pristine bit of the early solar system as it lost material while approaching the higher temperatures of the sun. With this knowledge, an international campaign to observe the comet was born. The number of space-based, ground-based, and amateur observations was unprecedented, including 12 NASA space-based assets observing Comet ISON over the past year.

Near the beginning of October, 2013, two months before perihelion, NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Observer, or MRO, turned its HiRISE instrument to view the comet during its closest approach to Mars in October 2013. "The size of ISON's nucleus could be a little over half a mile across --- at the most. Very likely it could have been as small as several hundred yards," said Alfred McEwen, the principal investigator for the HiRISE instrument at Arizona State University, in Tucson.

In other words, Comet ISON might have been the length of five or six football fields. This small size was near the borderline of how big ISON needed to be to survive its trip around the sun.

During that trip around the sun, Geraint Jones, a comet scientist at University College London's Mullard Space Science Laboratory in the UK studied the comet's dust tails to better understand what happened as it rounded the sun. By fitting models of the dust tail to the actual observations from NASA's Solar Terrestrial Observatory, or STEREO, and the joint European Space Agency/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO, Jones showed that very little dust was produced after perihelion, which may suggest that the comet's nucleus had already broken up by that time.

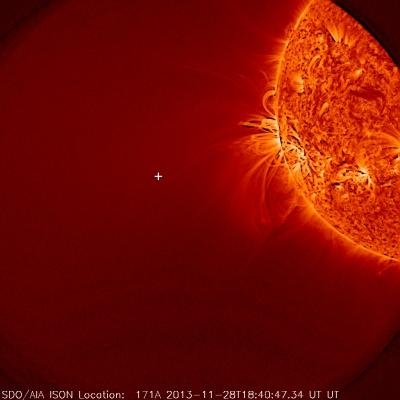

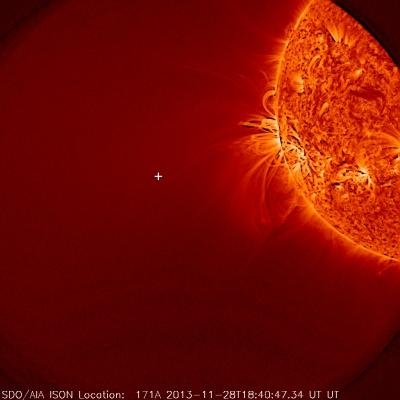

(Image from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory shows the sun, but no Comet ISON was seen. A white plus sign shows where the Comet should have appeared)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.02.24)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (05.02.24) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.02.24): Touchdown Zone Lighting

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (05.02.24): Touchdown Zone Lighting Aero-News: Quote of the Day (05.02.24)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (05.02.24) ANN FAQ: Contributing To Aero-TV

ANN FAQ: Contributing To Aero-TV NTSB Final Report: Cirrus Design Corp SR20

NTSB Final Report: Cirrus Design Corp SR20