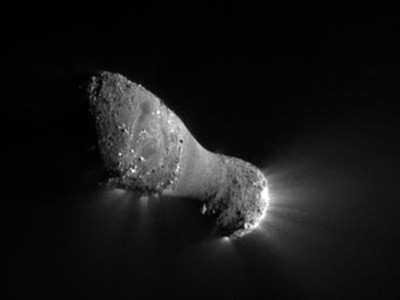

First Time To See Individual Ice Chunks In Comet Cloud

The EPOXI mission's recent encounter with comet Hartley 2

provided the first images clear enough for scientists to link jets

of dust and gas with specific surface features. NASA and other

scientists have begun to analyze the images.

The EPOXI mission's recent encounter with comet Hartley 2

provided the first images clear enough for scientists to link jets

of dust and gas with specific surface features. NASA and other

scientists have begun to analyze the images.

The EPOXI spacecraft revealed a cometary snow storm created by

carbon dioxide jets spewing out tons of golf-ball to

basketball-sized fluffy ice particles from the peanut-shaped

comet's rocky ends. At the same time, a different process was

causing water vapor to escape from the comet's smooth mid-section.

This information sheds new light on the nature of comets and even

planets.

Scientists compared the new data to data from a comet the

spacecraft previously visited that was somewhat different from

Hartley 2. In 2005, the spacecraft successfully released an

impactor into the path of comet Tempel 1, while observing it during

a flyby.

"This is the first time we've ever seen individual chunks of ice

in the cloud around a comet or jets definitively powered by carbon

dioxide gas," said Michael A'Hearn, principal investigator for the

spacecraft at the University of Maryland. "We looked for, but

didn't see, such ice particles around comet Tempel 1."

NASA Image Hartley 2 Comet

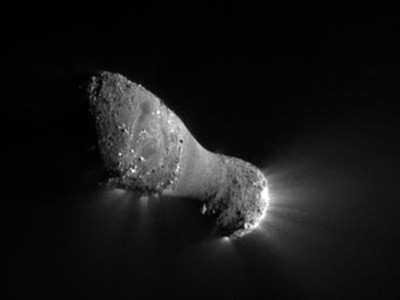

The new findings show Hartley 2 acts differently than Tempel 1

or the three other comets with nuclei imaged by spacecraft. Carbon

dioxide appears to be a key to understanding Hartley 2 and explains

why the smooth and rough areas scientists saw respond differently

to solar heating, and have different mechanisms by which water

escapes from the comet's interior.

"When we first saw all the specks surrounding the nucleus, our

mouths dropped," said Pete Schultz, EPOXI mission co-investigator

at Brown University. "Stereo images reveal there are snowballs in

front and behind the nucleus, making it look like a scene in one of

those crystal snow globes."

Data show the smooth area of comet Hartley 2 looks and behaves

like most of the surface of comet Tempel 1, with water evaporating

below the surface and percolating out through the dust. However,

the rough areas of Hartley 2, with carbon dioxide jets spraying out

ice particles, are very different.

NASA Image Hartley 2 Comet

"The carbon dioxide jets blast out water ice from specific

locations in the rough areas resulting in a cloud of ice and snow,"

said Jessica Sunshine, EPOXI deputy principal investigator at the

University of Maryland. "Underneath the smooth middle area, water

ice turns into water vapor that flows through the porous material,

with the result that close to the comet in this area we see a lot

of water vapor."

Engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, CA,

have been looking for signs ice particles peppered the spacecraft.

So far they found nine times when particles, estimated to weigh

slightly less than the mass of a snowflake, might have hit the

spacecraft but did not damage it.

"The EPOXI mission spacecraft sailed through the Hartley 2's ice

flurries in fine working order and continues to take images as

planned of this amazing comet," said Tim Larson, EPOXI project

manager at JPL.

Scientists will need more detailed analysis to determine how

long this snow storm has been active, and whether the differences

in activity between the middle and ends of the comet are the result

of how it formed some 4.5 billion years ago or are because of more

recent evolutionary effects.

NASA Image Hartley 2 Comet

EPOXI is a combination of the names for the mission's two

components: the Extrasolar Planet Observations and Characterization

(EPOCh), and the flyby of comet Hartley 2, called the Deep Impact

Extended Investigation (DIXI).

JPL manages the EPOXI mission for the Science Mission

Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. The spacecraft was

built for NASA by Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp., in

Boulder, Colo.

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (07.26.25): Downburst

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (07.26.25): Downburst ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (07.26.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (07.26.25) Classic Aero-TV: The Bizarre Universe of Klyde Morris Cartoons

Classic Aero-TV: The Bizarre Universe of Klyde Morris Cartoons ANN's Daily Aero-Term (07.27.25): Estimated (EST)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (07.27.25): Estimated (EST) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (07.27.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (07.27.25)