Controllers Say There Have Been Many Close Calls

With additional focus on airport congestion and the potential

for runway incursions, one of the first maneuvers any student pilot

learns is facing additional scrutiny by federal authorities: the

go-around.

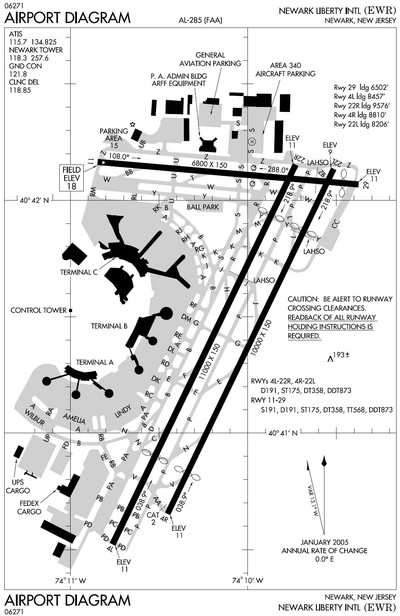

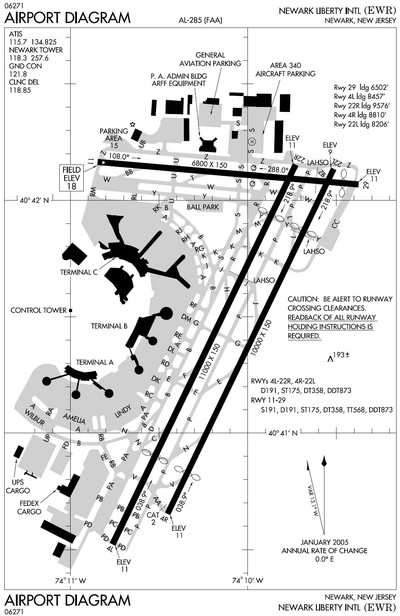

The Associated Press reports the FAA recently reviewed go-around

procedures at three of the nation's airports, including Newark

Liberty -- where the arrival ends for runways 22L, 22R and 29

intersect at the northeast corner of the field. Simultaneous

approaches to those runways can result in one or more go-arounds,

if the spacing isn't adequate.

Last year, authorities discontinued a go-around procedure used

at Detroit Metro, which sent planes landing on 27R directly into

the takeoff paths of aircraft on parallel runways 21R and 22L.

Similar changes were made in Memphis, after a Northwest DC-9

landing on runway 18R flew over a commuter plane going around on

intersecting runway 27 due to a mechanical issue. In that case,

controllers told the RJ to stay low over the runway, to avoid the

Northwest plane.

Go-arounds haven't been cited as the cause for any accidents or

midair collisions involving commercial airliners for over 30

years... but controllers are concerned about the close calls that

could have gone the other way. A review of tower logs at eight

airports conducted by the AP found over 1,500 go-arounds in the

last six months of last year.

"We can go 99 percent of the time and not have a problem. But it

only takes one," said John Wallin, president of the Memphis branch

of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association.

The overwhelming cause of go-arounds has to do with improper

spacing -- an aircraft on final approach is too close to landing

traffic ahead, or a plane that hasn't yet cleared the active.

That's a particular problem at the nation's busiest airports, where

planes land and depart as often as every two minutes.

Shifting winds can also lead to go-arounds, as can runway

incursions by taxiing aircraft or ground vehicles. And, usually,

they're a non-event, stressed 20-year airline pilot Ralph

Paduano.

"We're trained in that maneuver, so it's not a tense situation,"

said Paduano, who now flies for Continental. "But you have to

really be on the ball; you can't be complacent about it."

Pilots are familiar with the mechanics of a go-around; whether

in a single-engine Cessna or a Boeing 747, the forces at work are

the same. Pilots must quickly reconfigure a "dirty" plane -- flaps

and slats out, traveling low and slow on approach to the runway --

to fly again. In a commercial airliner, flight crews must also

factor in the lag time for turbofan powerplants to spool up to

full-power.

At Newark, nearly half of the close

to 300 go-around recorded between August 2007 and January 2008 were

caused by runway "ties," with planes approaching intersecting

runways at the same time and at roughly the same spacing. To avoid

potential conflicts, controllers at Newark have taken to

"staggering" arrivals on intersecting runways.

At Newark, nearly half of the close

to 300 go-around recorded between August 2007 and January 2008 were

caused by runway "ties," with planes approaching intersecting

runways at the same time and at roughly the same spacing. To avoid

potential conflicts, controllers at Newark have taken to

"staggering" arrivals on intersecting runways.

"You have about eight miles, or about two minutes, to figure it

out and make it work" after approach control hands off a landing

aircraft to the tower, said Ray Adams, vice president of the

controllers union at the airport. "It comes down to how busy you

are and what your skill level is. You have to make some serious

moves pretty early to get the sequence to work out."

At the behest of the Department of Transportation's Inspector

General, the FAA is now reviewing landing procedures at Newark. So

far, the FAA told the AP, it's "found no safety issues" since the

staggering procedure was implemented last year.

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.30.25)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.30.25) ANN FAQ: Turn On Post Notifications

ANN FAQ: Turn On Post Notifications Classic Aero-TV: Agile Aeros Jeff Greason--Disruptive Aerospace Innovations

Classic Aero-TV: Agile Aeros Jeff Greason--Disruptive Aerospace Innovations Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.30.25)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.30.25) ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.30.25): Expedite

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.30.25): Expedite